On March 6–7, 2026, Grace Church of the Nazarene hosted the first Nashville Maker’s Space, a collaborative event bringing together churches using design thinking to experiment with new ways to include neurodivergent children and families in the life of the church through worship and prayer. Rather than presenting finished programs, the gathering invites congregations to share prototypes—early ideas shaped by real experiences with children in their communities.

The Maker’s Space model encourages churches to begin with stories: a child who struggles to sit still during worship, a family that stopped attending because there was nowhere for their child to go during sensory overload, or a moment when a child revealed a spiritual insight adults had overlooked. From these experiences, leaders design small experiments that help congregations rethink prayer, worship, learning, and belonging.

Throughout the time, key consultants guide the deliberation including Ryan Nelson, Nazarene Disability Ministries National Coordinator, Kayla Smith with Reaching Hurting Kids Institute, Brad Lee Director of Special Needs Family Institute and Dr. Dana Preusch, national Nurturing Care Coordinator and spiritual director. The combination of expertise displayed among the consultants allowed these leaders to listen into the planning without undue interference but still offer a wealth of professional experience and guidance.

Across the projects presented in Nashville, churches have organized their work around four themes: Prayer, Inclusive Worship, Deepening Formation, and Changing Congregational Mindset. Each theme reflects a different way congregations are learning from neurodivergent children and adapting their practices so that every child can participate fully in the life of faith.

Prayer

Several churches in the Maker’s Space are exploring how prayer can become more accessible through creativity, movement, and sensory engagement. Their proposals challenge the assumption that prayer must always be verbal or still, suggesting instead that children may connect with God through play, objects, or expressive actions.

Pine Hill Church

Pine Hill Church’s project grows from the experience of a child who struggles with the expectation of sitting quietly through a 30-minute family worship service. Leaders are developing “Sprout Boxes,” containers filled with prayer prompts, journals, sensory tools, and visual prayer guides that help children participate during worship rather than simply being distracted. The goal is to move beyond keeping children busy and instead give them tools for spiritual engagement. As one leader explained, the hope is to create ways “to assist our little friend in being able to be a part of that table that’s already there in meeting his God in those services.”

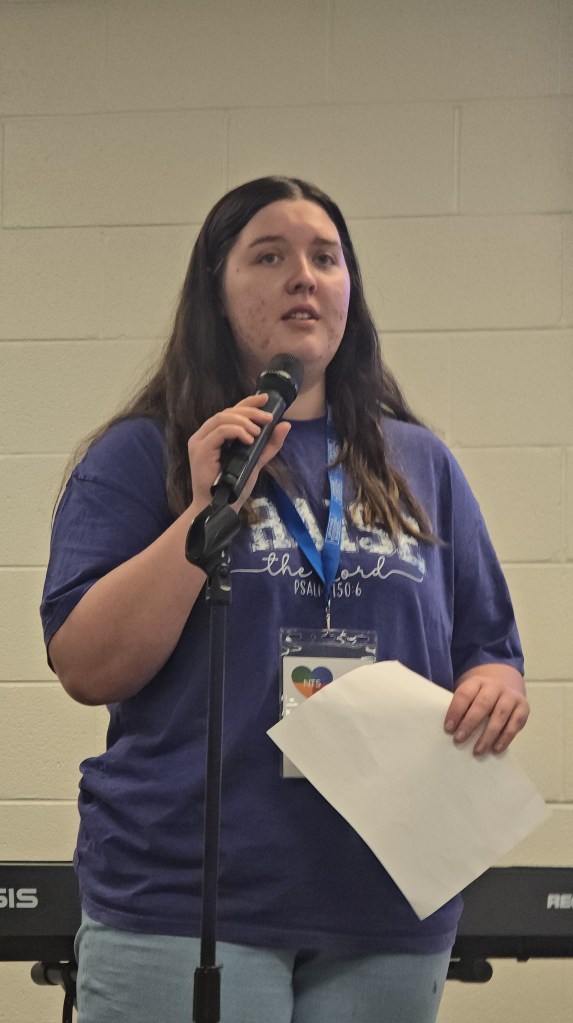

Refinery Church

Refinery Church’s project is inspired by a child who rarely speaks but once surprised his leaders by climbing onto the platform and sharing what he had learned in children’s church. The moment revealed that Jacob had insights worth hearing but needed different ways to express them. In response, the church is experimenting with creative forms of prayer such as journals that combine drawing and writing, prayer walks, expressive actions, puppets, and prayer jars. The goal is to make prayer accessible to children with different communication styles and abilities. As the project leader noted, the aim is to “create opportunities and help Jacob feel more comfortable and confident in prayer.”

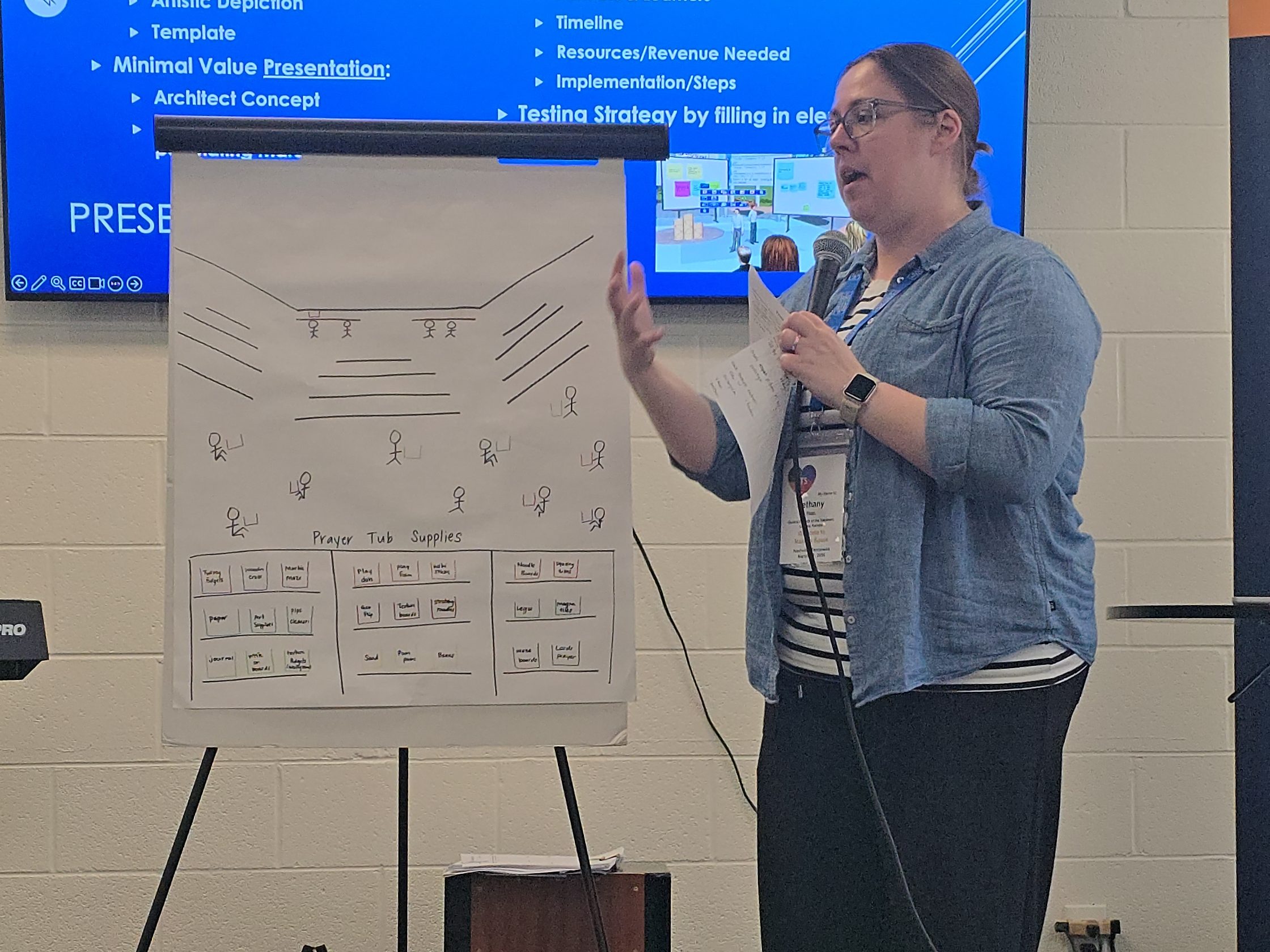

Lenexa Central Church

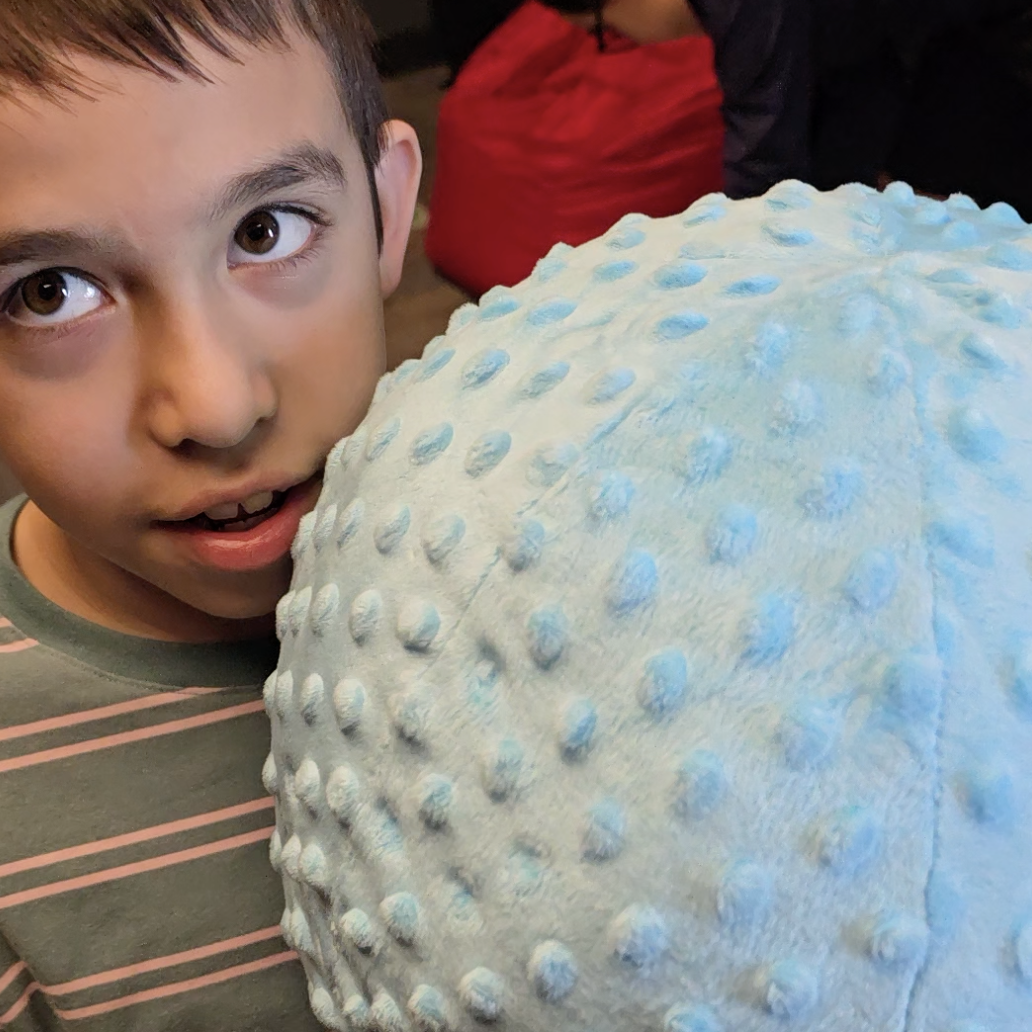

Lenexa Central’s proposal focuses on helping children engage the culture of church through sensory prayer bins, containers filled with tactile objects such as Play-Doh, markers, and prayer prompts. During a dedicated prayer period in children’s worship, kids select materials and find a quiet place to pray, often expressing their prayers through play or drawing. The idea emerged from the story of a child who loved coming to church but struggled to participate meaningfully in its practices. As the project leader explained, the goal is to create a space where children can connect with God through sensory engagement: “while they’re playing, the idea is that they will also be praying.”

Inclusive Worship

Another group of churches is focusing on how the structure of worship itself can become more inclusive. These projects explore ways children can lead, participate, and remain in the sanctuary alongside their families rather than being separated from the congregation.

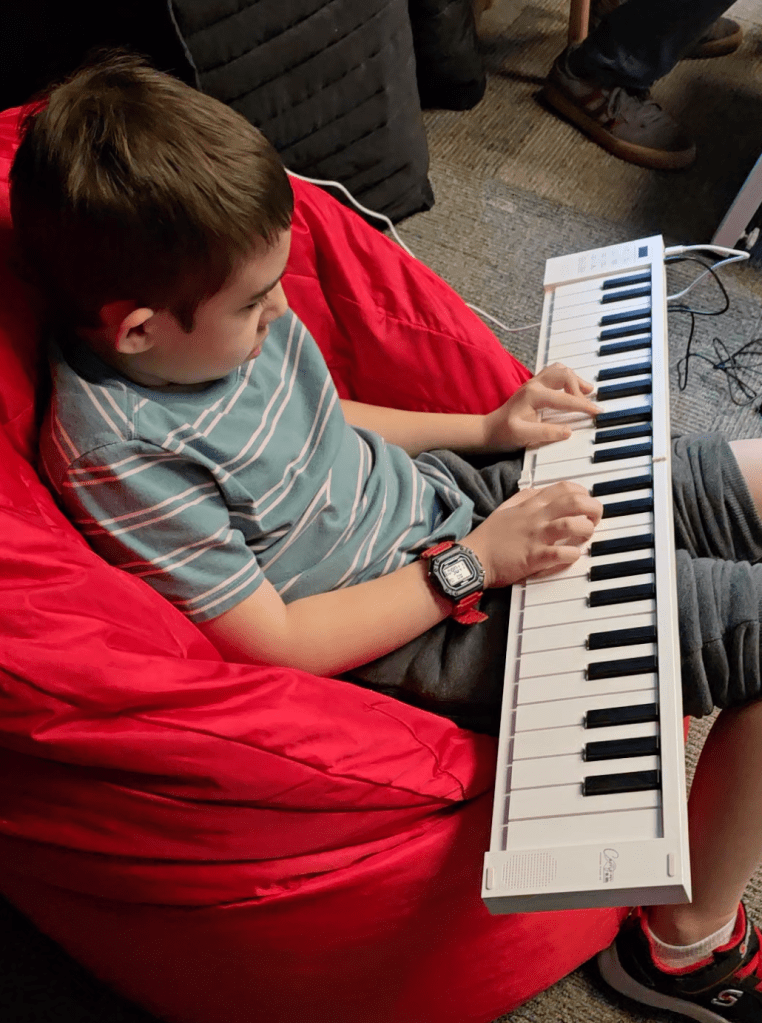

Las Palmas Church

At Las Palmas, the project is deeply personal, emerging from a parent’s desire to create a welcoming worship environment for her son Jonathan and other children with disabilities. The church hopes to transform an existing children’s room into a multisensory worship environment filled with music, instruments, videos, tactile objects, and calming areas where children can explore faith through play. The vision is not merely to entertain children but to help them internalize Scripture and worship freely. As the project leader described her motivation, she wants a place where her son can feel that church “is my second home… a place where he would feel comfortable.”

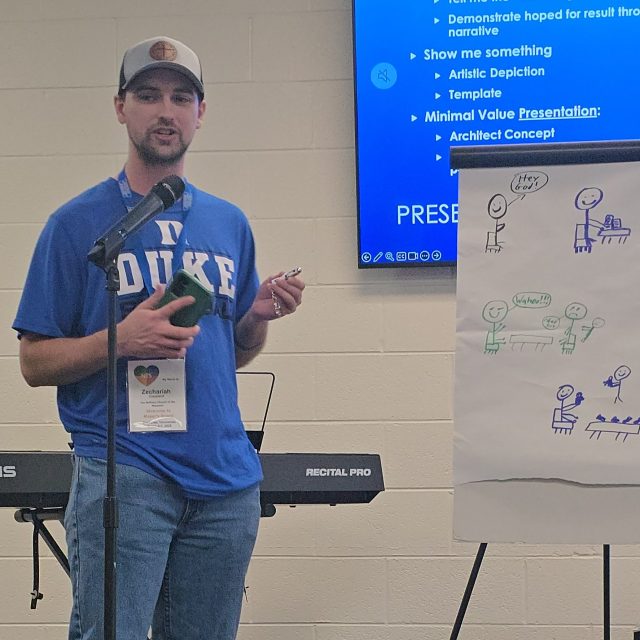

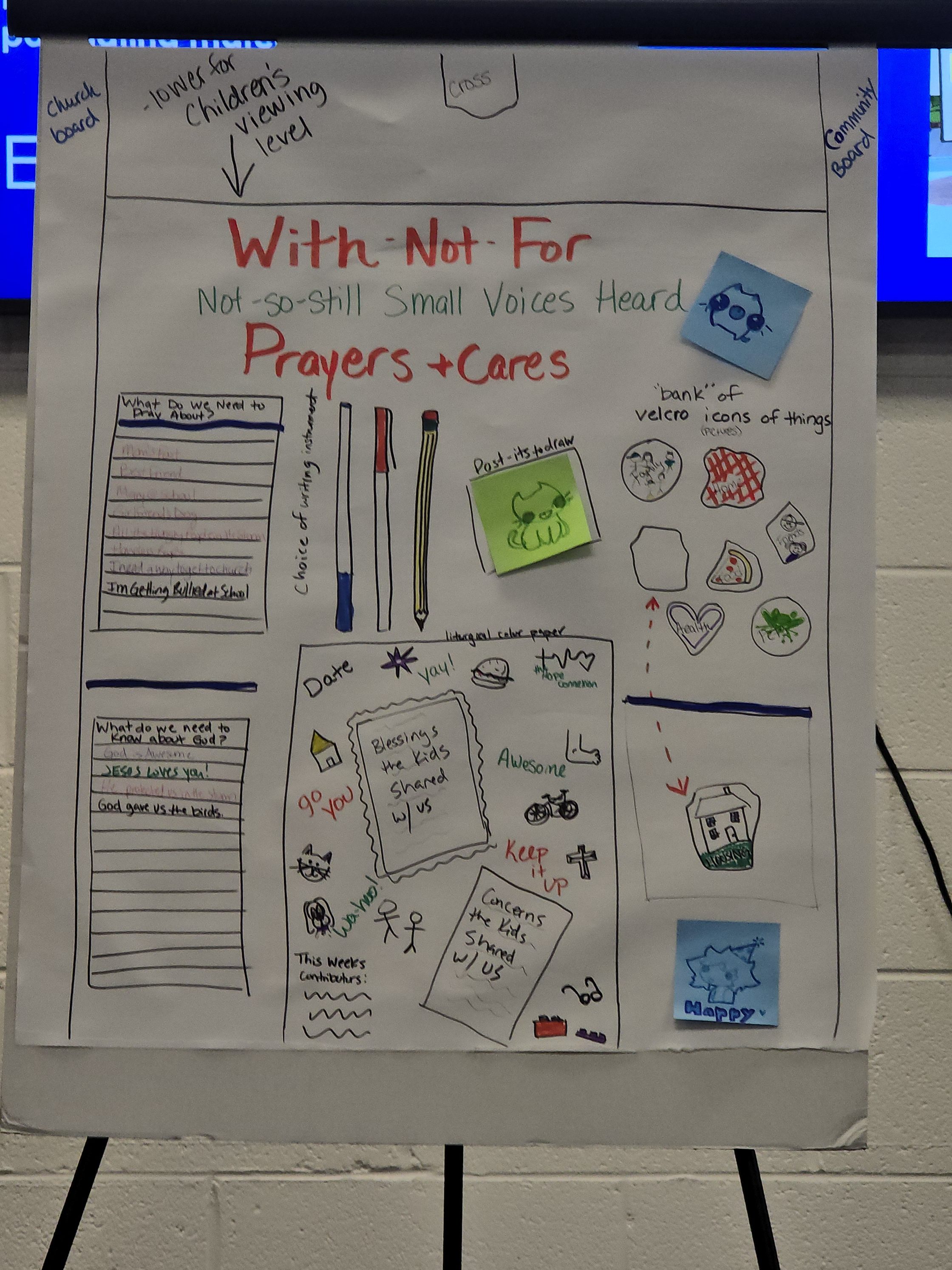

Hope Connextion Church

Hope Connextion’s proposal invites children into a more active role during worship by giving them responsibility for creating and leading portions of the service. A creative team composed of teens and young adults—many with personal experience with autism—will help children design weekly prayer bulletins and share their concerns with the congregation. The project emphasizes that children’s voices can shape the spiritual life of the church. Leaders hope that by highlighting children’s prayers, the congregation will see their role in the church more clearly and recognize their contributions to God’s work. The goal, organizers say, is to “show the adults a little glimpse into their hearts.”

Liberty Church

Liberty Church’s project emerged after a family with two daughters with special needs stopped attending because the congregation lacked appropriate accommodations. Determined to welcome them back, leaders are designing an inclusive worship space in the back of the sanctuary that allows children to move, fidget, or engage creatively while remaining part of the service. The area will include sensory tools, flexible seating, and a Lego wall where children can express ideas about God. The design intentionally allows children to move between the sensory area and the sanctuary as needed. The aim, leaders say, is to ensure that families know “they can still be part of worship, that they belong with us.”

Deepening Formation

For several congregations, inclusion is not only about access but also about spiritual formation. These churches are experimenting with environments and practices that help children process faith experiences more deeply.

Oxford Church

Oxford Church’s initiative grew from relationships rather than formal outreach. One such relationship began at a birthday party, where church members met Vivian, a child on the autism spectrum. When Vivian eventually visited the church, the congregation embraced her expressive behaviors during worship, creating a sense of belonging that encouraged her family to stay. Building on that experience, the church plans to redesign classroom spaces with sensory elements, calming corners, and updated curriculum that helps children remain engaged during lessons and cultivate a deeper sense prayerful engagement. Leaders say the church’s openness to Vivian’s presence made a lasting impact: her family appreciated how the congregation “took to their daughter Vivian… and just fit right in.”

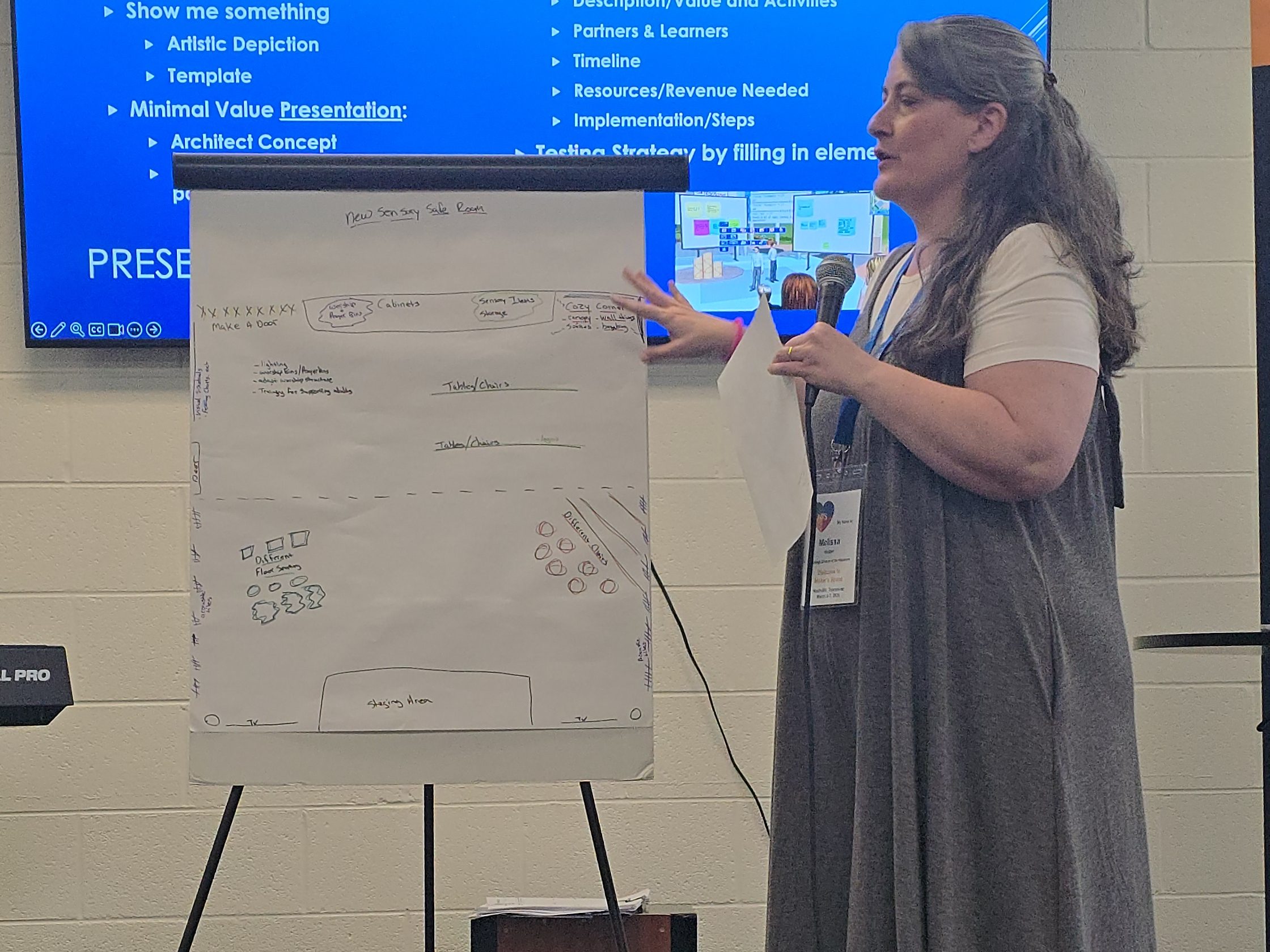

Hermitage Church

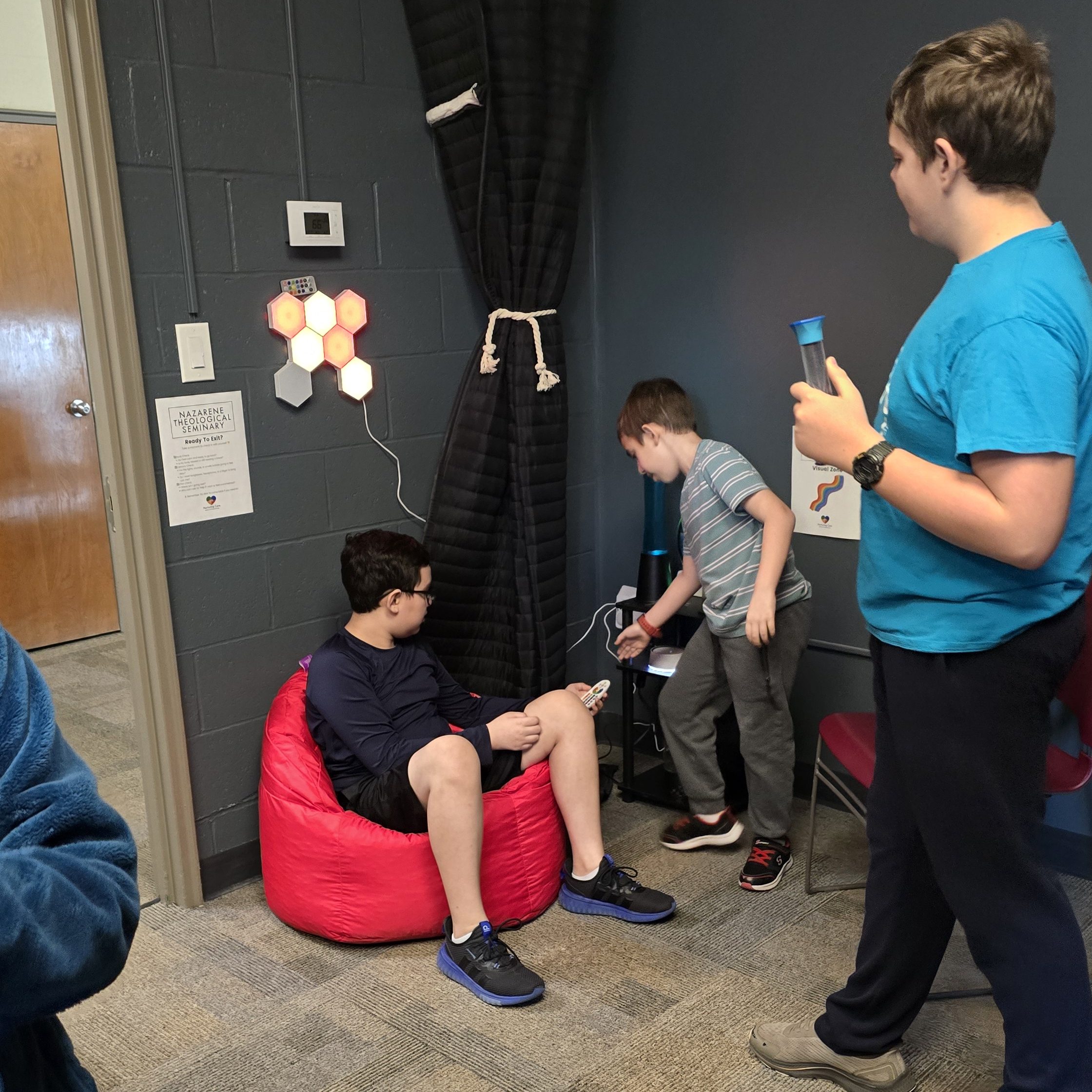

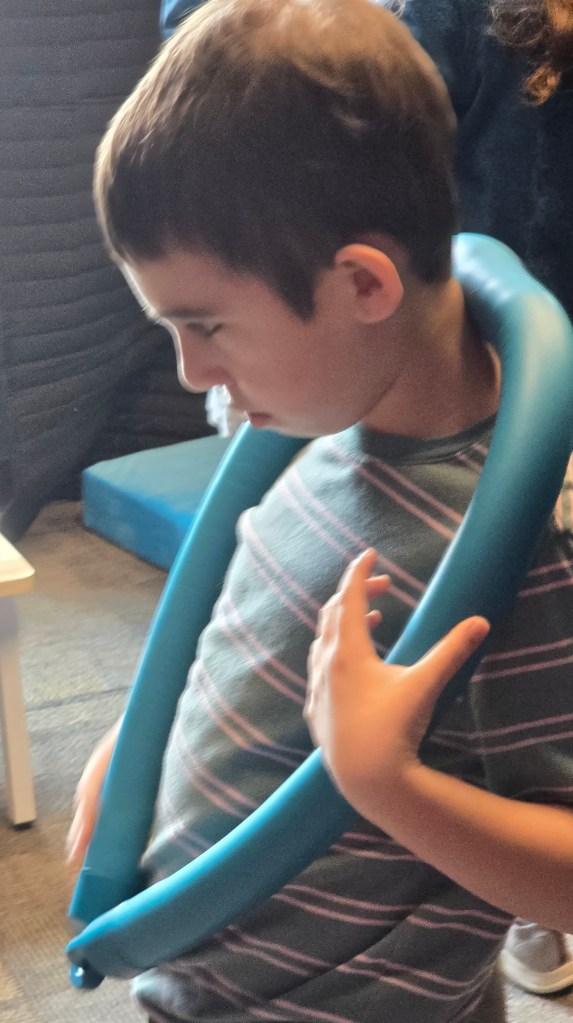

Hermitage Church’s project addresses the physical environment of children’s ministry. Leaders realized the need for better support after observing two children who responded differently to sensory overwhelm—one needing a quiet corner and another requiring complete separation from the room. Their proposal redesigns the ministry space with acoustic improvements, better lighting, varied seating, and designated zones for worship and activity. Ultimately, they hope to create a sensory-safe room that allows children to regulate their environment without being sent into a hallway. The guiding principle behind the redesign is simple: “I want to invite children to worship God just as they are.”

Changing Congregational Mindset

The final group of projects moves beyond individual programs and focuses on changing the culture of the church itself. These proposals emphasize hospitality, awareness, and structural changes that help congregations rethink disability and belonging.

Lovejoy Church

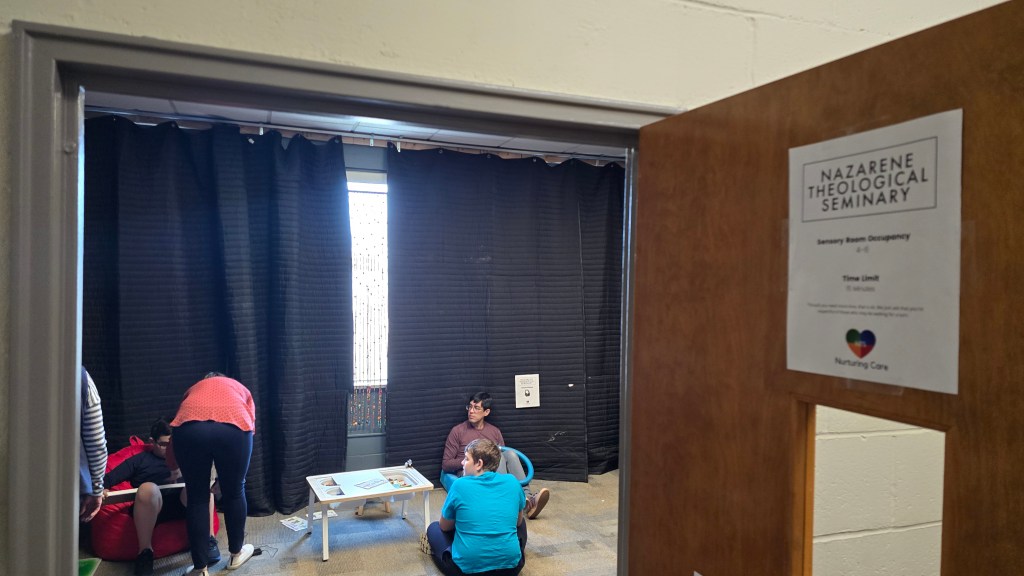

Lovejoy Church begins its project with a striking observation: there are currently no known children with disabilities attending the congregation. For leaders, that absence signals a deeper problem. With tens of thousands of families with disabilities living in the surrounding county and fewer than 10 percent attending church, the congregation sees a clear opportunity for outreach. Their proposal centers on creating a sensory room equipped with calming lighting, tactile toys, and streaming access to the service so families can remain connected to worship. As the project leader reflected, the church must respond to the biblical call to serve vulnerable families, noting that “whatever we do for the least of these, we do for Him.”

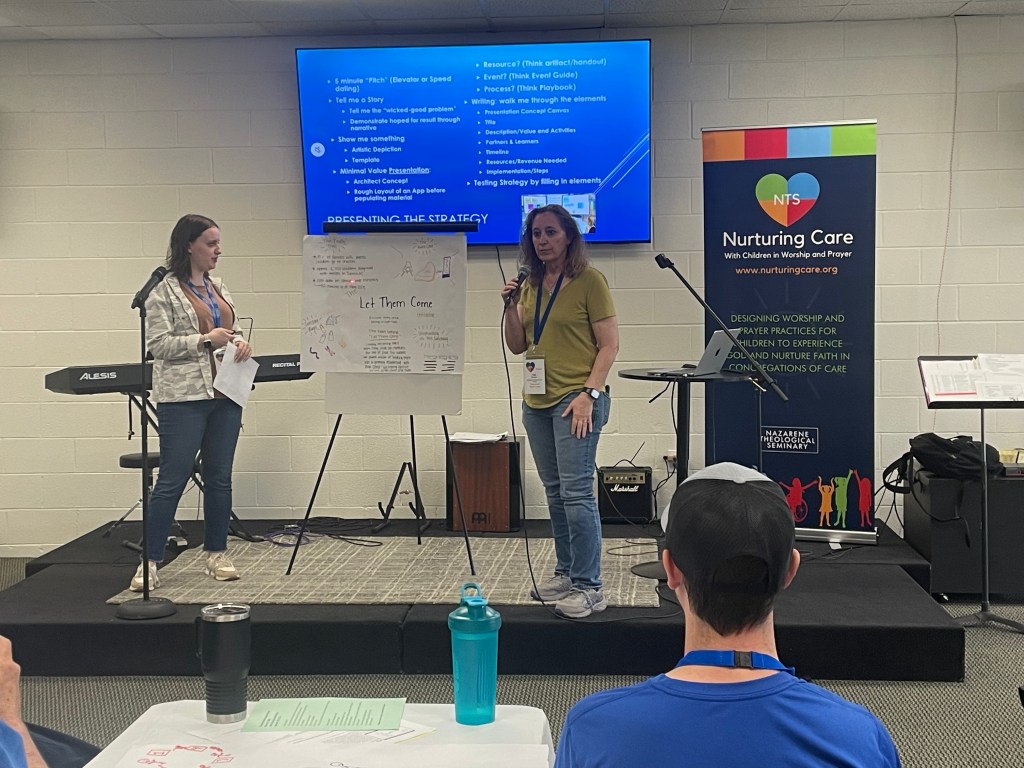

Wannamaker Woods Church

The “Let Them Come” initiative at Wannamaker Woods seeks to reshape how the church understands disability and inclusion. Drawing from personal experiences raising children with diverse needs, the project highlights the large number of families with disabilities who currently do not attend church. The initiative proposes several practical changes—including sensory rooms, family quiet spaces, and sensory-friendly seating in the sanctuary—while encouraging members to rethink assumptions about visible and invisible disabilities. As one leader explained, the church hopes to remind people that “just because a child looks a certain way doesn’t mean that they function a certain way.”

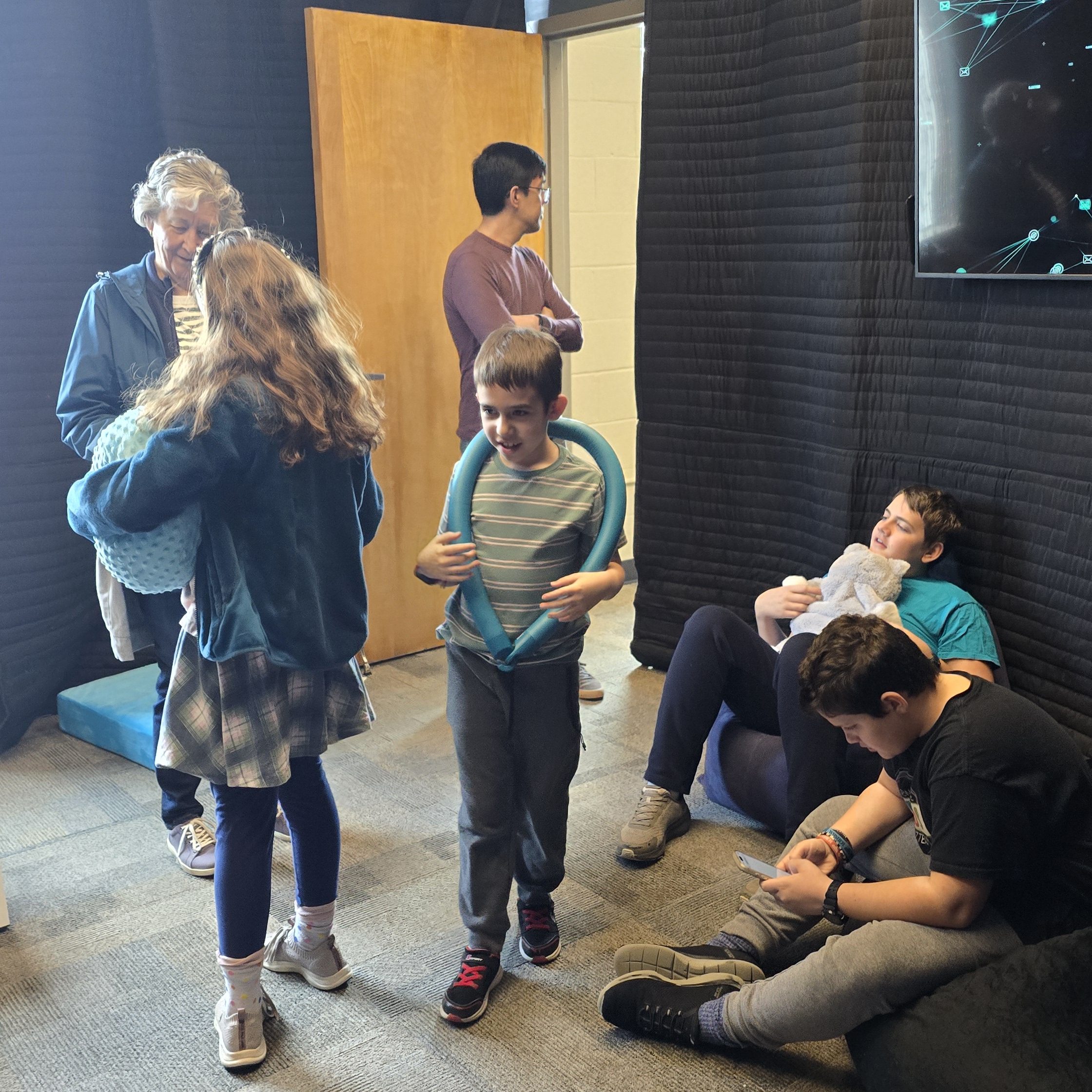

Grace Church of the Nazarene

Grace Church, the host of the Nashville Maker’s Space, is proposing a Safe Space Sanctuary designed for families who need flexibility during worship services. The room will feature sensory elements, comfortable seating, and televisions streaming the sermon so caregivers can remain engaged even while attending to their children. The idea arose from the leader’s own experience of stepping out of services and missing the message. By creating a space where families can stay present in the building, the church hopes to remove one of the barriers that keeps many special-needs families from attending. As the organizer explained, the goal is simple for any parent: “to hear the sermon instead of just streaming it from home, they can actually still be here.”

Together, these projects illustrate how congregations are learning from the experiences of neurodivergent children and their families. Nurturing Care Director, Dr. Dean G. Blevins noted the Nashville Maker’s Space is not simply about generating new programs; it is about reimagining how churches pray, worship, and learn together. By beginning with real stories and testing practical ideas, these congregations hope to create communities where every child can find their place at the table of faith.