A growing network of midwest congregations are redesigning children’s ministry and worship spaces to better welcome children with autism, ADHD and other sensory needs. A recent meeting, coupled with several written updates, revealed churches pairing practical tools like flexible seating and sensory rooms with volunteer training and shared learning across churches. In addition Nurturing Care announced its next Day of Learning with Melody Escobar on April 13 (see below)

At Second Presbyterian Church in Kansas City, leaders say the most visible change isn’t a single tool—it’s how the congregation is learning to make room for children as full participants. In worship, older adults are growing more comfortable with babies crawling and kids moving in the sanctuary, while teens join preschoolers in a “pray-ground” space using a visual children’s bulletin and shared sensory bins. The report notes that even without a specific autism-focused story in this month’s update, the goal is to normalize welcome so families who arrive later “can belong exactly as they are.”

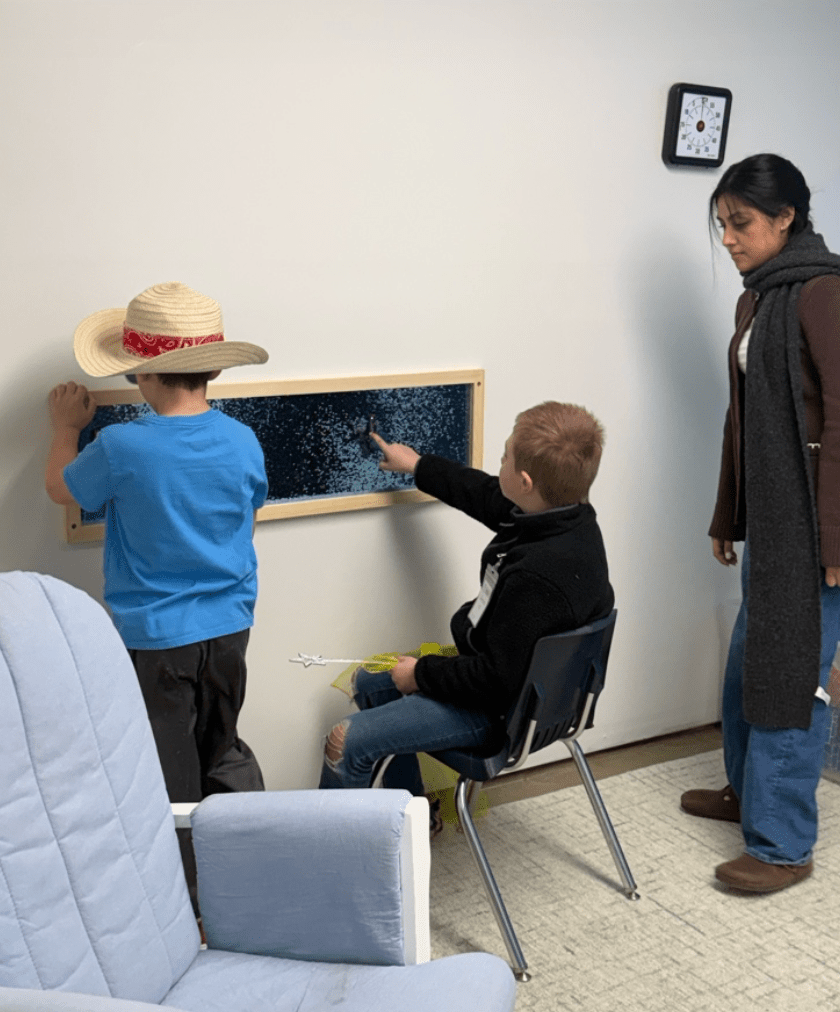

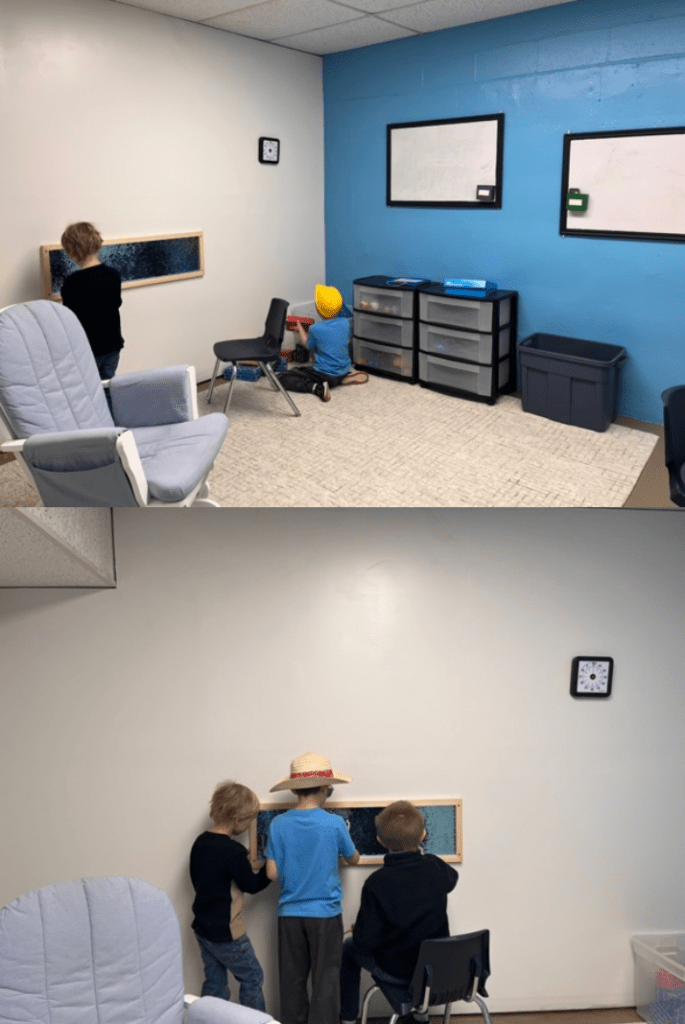

Other congregations are seeing how small accommodations can reshape a child’s experience of worship. At New Hope Church of the Nazarene, leaders described supporting an autistic child with a rubber seat topper, simple directions, and a consistent buddy—changes they said helped the child remain calm and participate more fully, including staying through songs and clapping at the end rather than leaving mid-service. The congregation has also built a sensory-friendly “Blue Room,” allowing children to explore wall-based sensory features and a buddy-system approach in action.

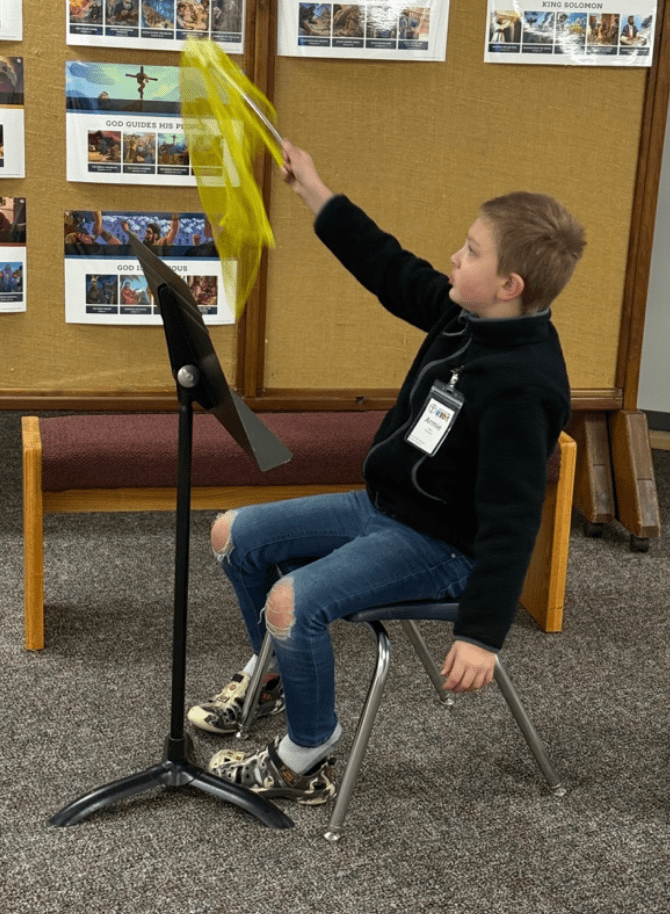

At Raymore New Vision Church of the Nazarene, a balance board became a turning point—not only for a student who previously struggled to answer discussion questions, but for an adult volunteer who had been hesitant about the prototype. After seeing the student engage more effectively while using the board, the volunteer told leaders they were “more on board,” the report says. Leaders also noted that as they identify which fidgets are too loud or used in unintended ways, congregants are responding positively to the adaptive process—and some adults have even expressed curiosity about trying the tools themselves.

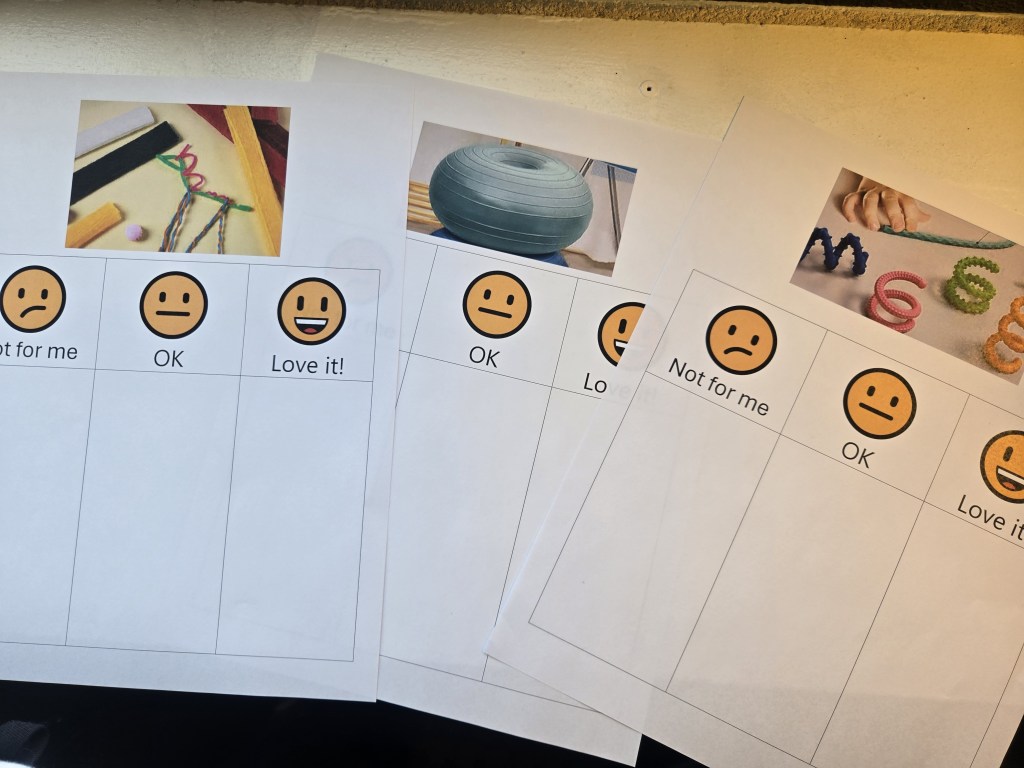

Several churches emphasized that introducing sensory supports also requires teaching boundaries and expectations—especially when kids love the tools for reasons beyond their intended purpose. At Christ Community Church of the Nazarene, leaders launched an “Engaging Movement” initiative by purchasing sensory items, flexible seating, and fidgets, then created a visual, emoji-based survey so pre-readers could still give feedback during children’s worship prayer stations. Early trials were promising, but the report flagged a familiar challenge: children gravitating toward donut chairs as if they were riding toys—prompting leaders to prioritize training so the supports lead to deeper connection rather than simple distraction.

At Westside Church of the Nazarene in Olathe, leaders said they have “dramatically adjusted” the worship space by limiting overstimulating activities—such as ball games—and replacing them with quieter, more interactive options, along with expanded seating choices that give children more agency while still maintaining expectations for participation. Volunteers have noticed the difference, including one Sunday school teacher who reported kids arrived more ready to engage after children’s worship in the updated environment.

Across the cohort, leaders are also turning toward more formal training. An 8th Street grant report described a shift “from observation to conversation,” as kids-ministry volunteers asked for skills-based support to better serve neurodivergent children and those carrying trauma. The team is now planning a congregational training with a neurodiversity professional, aiming for March, and discussing opening it to the wider church to strengthen a shared culture of care.

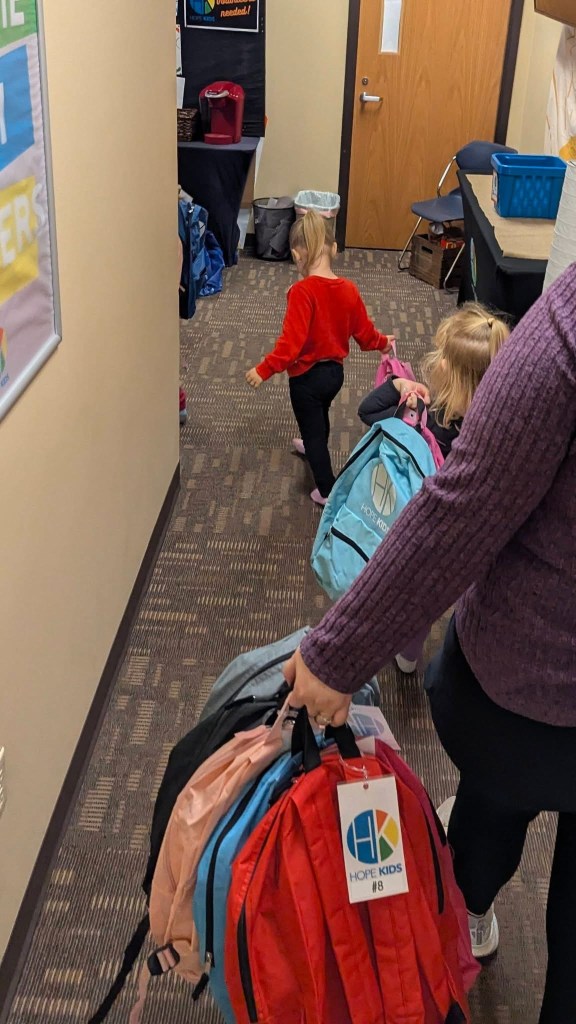

That learning mindset is showing up in hands-on preparation, too. At Living Hope Church, children of multiple ages are helping pack “backpacks” of supports for Sunday worship—an effort leaders hope will form long-term expectations of inclusivity among the next generation of volunteers. The report also describes upcoming classroom walk-throughs, a new teacher’s manual for volunteers, and a moment when a long-time volunteer shifted a struggling student’s behavior by assigning “leadership tasks,” underscoring how relational strategies can work alongside sensory tools.

In similar fashion Norman Community Church also unveiled their mobile sensory bag station. Pastor Nathan Jenkins and lay leader Wesley Grippen noted that they have had nothing but compliments about this bold display, but the favorite reaction has been that of the kids. While possessing the mobile sensory bags for some time, but they had been somewhat of an afterthought with no prominent placement. Jenkins observed: “The first Sunday we had the shelves up, the kids surrounded them as they had the chance to ‘customize’ and ‘personalize’ their bags. One kid even said, ‘This is the best day ever!’”

Norman Community church also includes a hybrid sensory space. Leaders in the Nurturing Care cohort reported that the work has moved beyond purchasing supplies to building a culture of belonging: creating calmer environments, training adults to respond differently to overstimulation, and swapping ideas—from weighted stuffed animals and sensory boards to safety lessons about how tools are used.

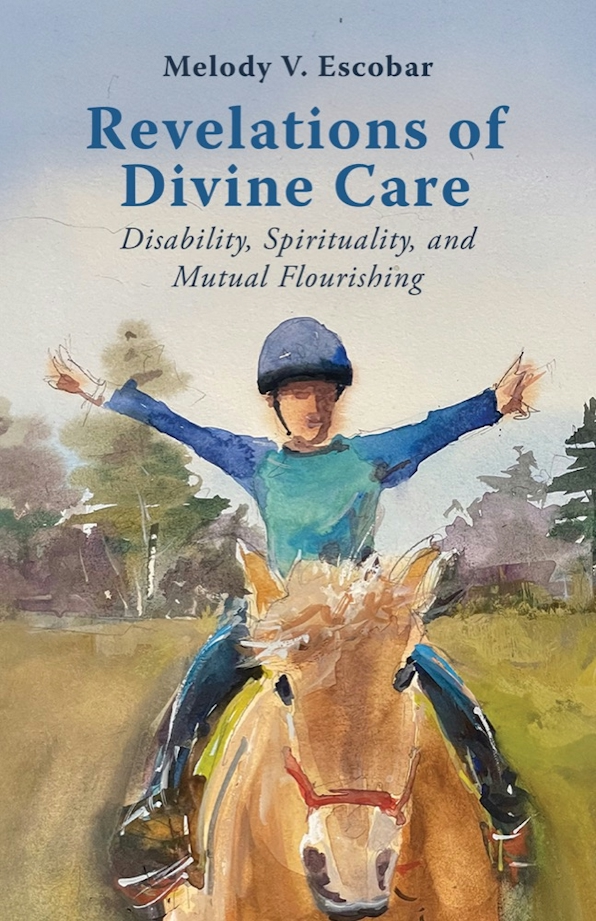

Organizers are also planning collaborative next steps, including a possible sensory-room open house and an “Day of Learning” on April 13 titled Revelations of Divine Care: Welcoming and Caring for Autistic Members in the Life of the Church. The event will take place at Nazarene Theological Seminary and offered online, featuring Dr. Melody Escobar from Baylor’s Center for Disability and Flourishing. Dr. Escobar, author of Revelations of Divine Care: Disability, Spirituality, and Mutual Flourishing, will draw from Julian of Norwich’s theology of God’s tender, adaptable care and contemporary autism ministry research, Melody will share her family’s journey—from years behind the cry room glass to their autistic son’s First Communion—and invite participants to explore practices, postures, and possibilities that can nurture deeper belonging within their own communities present

Taken together, the January updates show a cohort learning in real time: celebrating progress, naming safety and training needs, and building a shared calendar of ways to keep widening the circle of belonging—one seating option, sensory space, and volunteer conversation at a time.