In a recent webinar session of the West Coast initiative on virtue formation, Dr. Ross A. Oakes Mueller provided a profound exploration of compassion. Dr. Oakes Mueller serves as psychology professor at Point Loma Nazarene University (PLNU) and as a Nurturing Care consultant in partnership with the PLNU Center for Pastoral Leadership. Dr. Oakes Mueller’s goal was to move participants from a simplistic understanding of compassion through its scientific and psychological complexity to reach a deeper, more practical simplicity on the other side.

The Motivational System: Values vs. Virtues

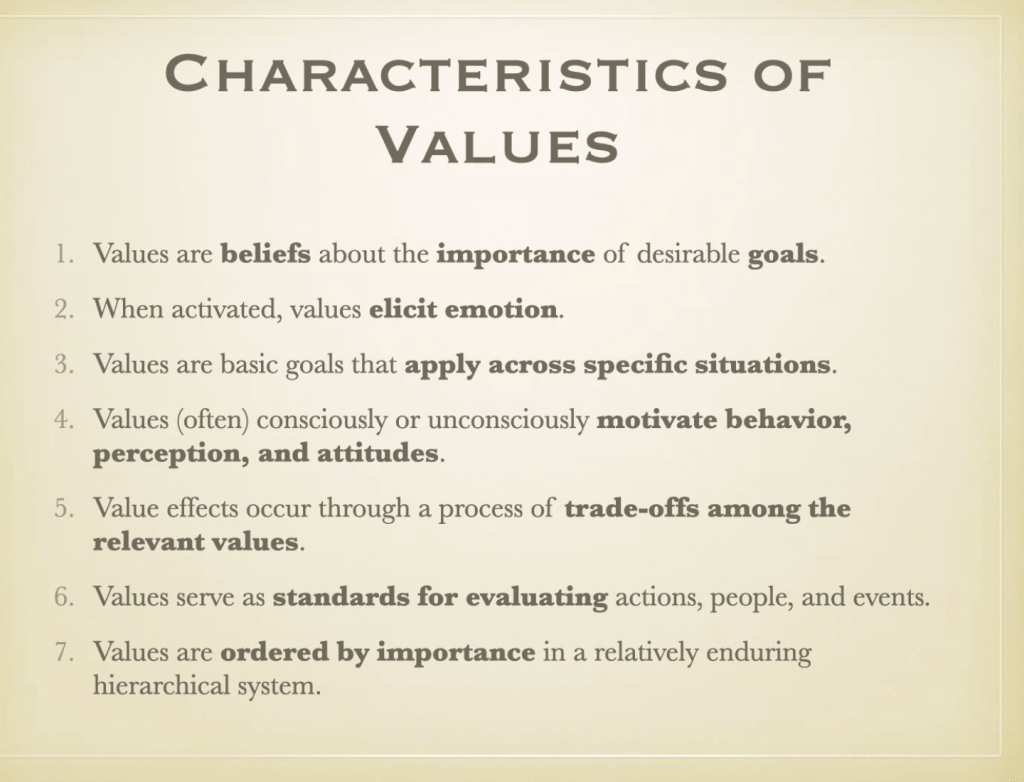

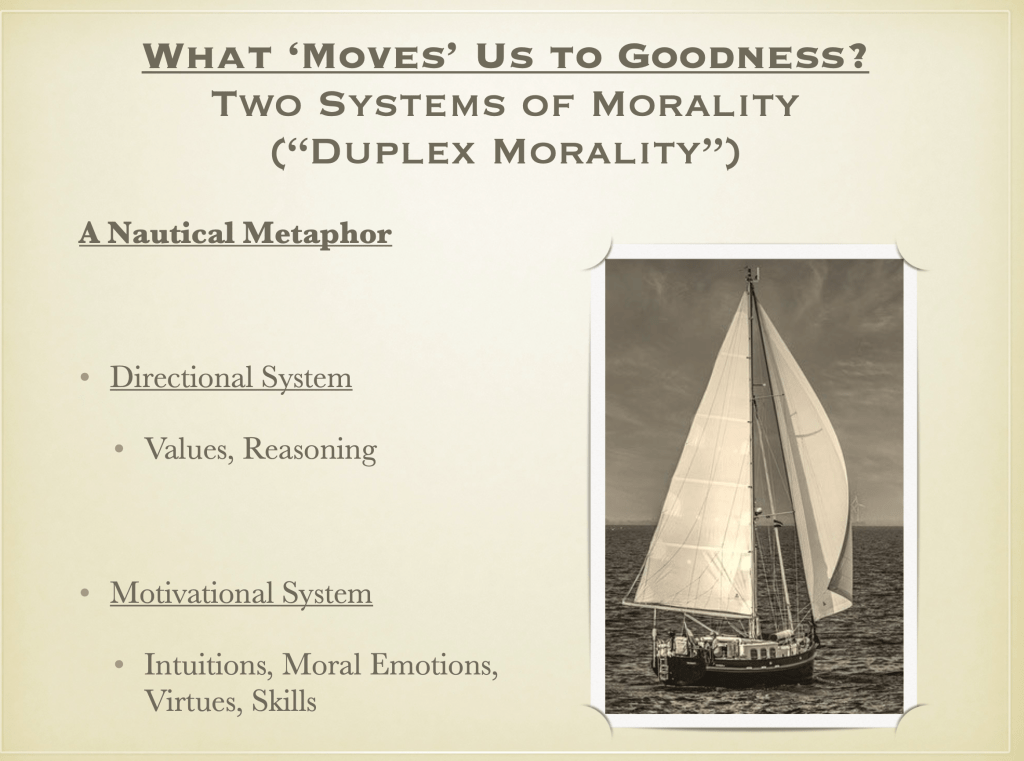

One of the most salient insights for ministry is the distinction between a value and a virtue. Dr. Oakes Mueller defines values as “cold cognitions”—rational, trans-situational goals that serve as our “directional system.” For many ministers, it is easy to teach the value of neighbor love, yet we often witness a “values-action gap” where well-meaning individuals fail to act in moments of crisis. A virtue, by contrast, is a habit of attention, desire, emotion, and behavior acquired through intentional practice.

Dr. Oakes Mueller also offered an analogy for understanding the difference between values and virtues: Think of a sailing vessel embarking on a voyage. Your values are the compass and the charts that mark the destination; they tell you where you ought to go. However, a ship without wind remains stationary. Virtues are the wind filling the sails; they are the habituated, emotional drives that provide the actual power to move the ship toward the goal of neighbor love.

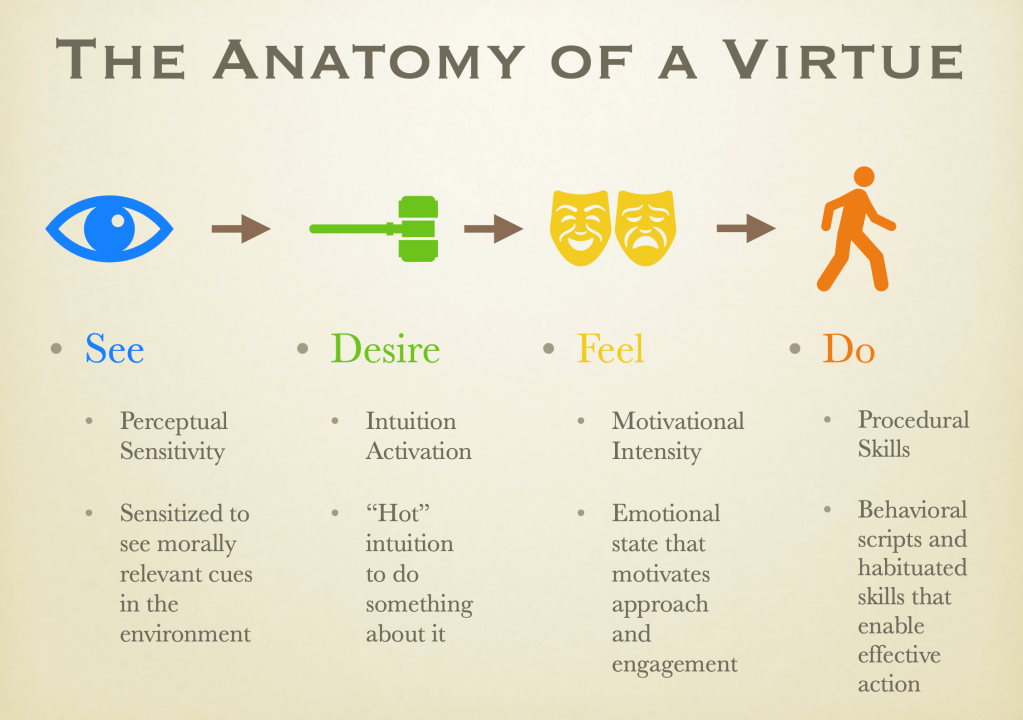

The Four Facets of the Virtuous Life

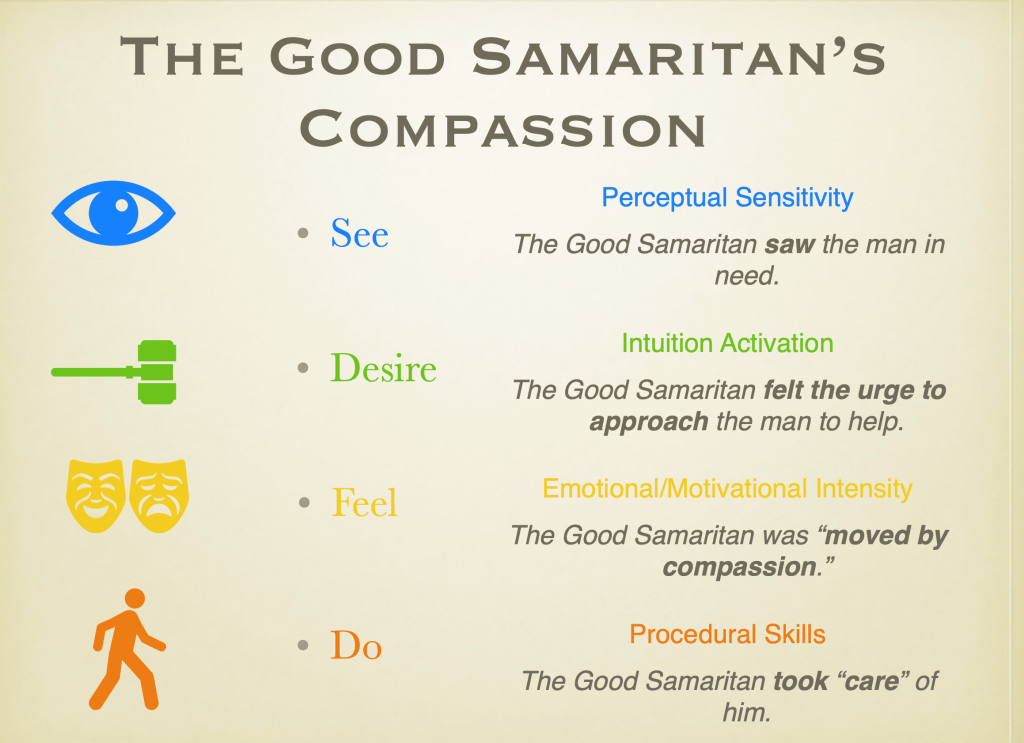

To move from valuing compassion to embodying it, Dr. Oakes Mueller identifies four key facets:

See: Developing a moral lens to perceive suffering.

Desire: A “hot intuition” or gut feeling that something must be done.

Feel: A specific emotional state of warmth and sadness that provides motivational intensity.

Do: Possessing the procedural skills or “behavioral scripts” to act effectively.

Using the parable of the Good Samaritan, Dr. Oakes Mueller illustrated how the Samaritan—unlike the priest or Levite—possessed the habituated skills to see the man, move toward the injured person, feel moved by compassion, and execute medical and financial aid.

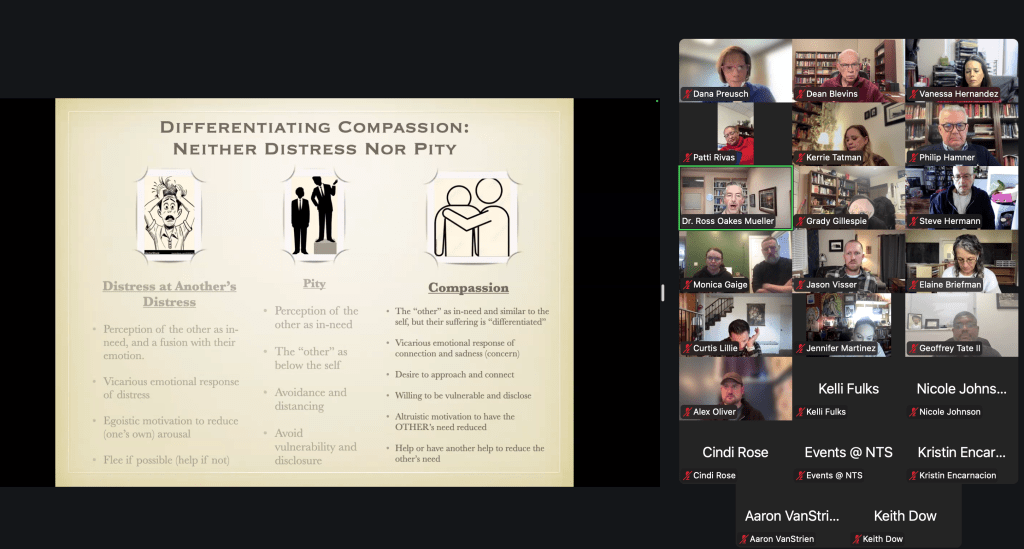

The Power of Self-Other Differentiation

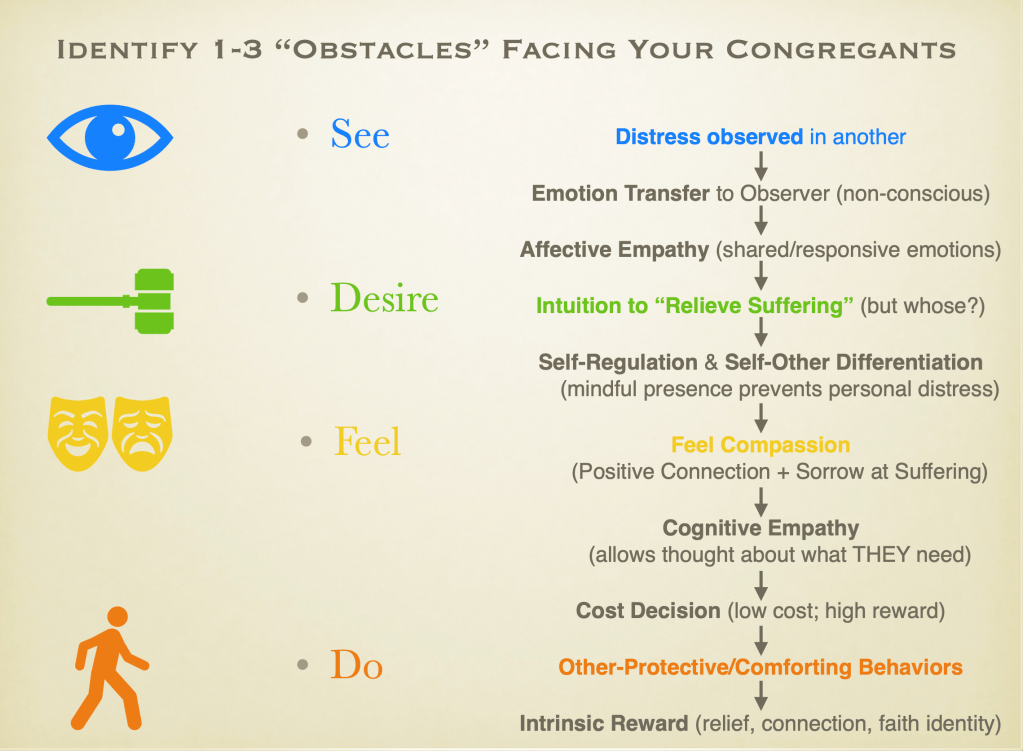

A second vital insight for those in caregiving roles appears in the necessity of self-other differentiation. True compassion must be distinguished from “distress at another’s distress” (DAAD), where care givers fuse emotionally with a victim and become overwhelmed. When carers “feel exactly what they feel,” their self-involved motivation compels them to reduce their own arousal, which often leads caring people to flee or numb out to protect themselves.

Virtuous compassion requires presence and mindfulness—the ability to see suffering as valid and real while remaining differentiated from it. By maintaining this boundary, caring people avoid “empathy fatigue” and remain capable of an approach-oriented response that seeks the other’s relief rather than their own escape.

Identifying the Barriers: Why Compassion Fails in Our Pews

While most congregants hold the value of compassion in high regard, there remains a persistent “values-action gap” where the actual enactment of neighbor love fails. In his second session on virtue formation, Dr. Ross Oakes Mueller explored the complex psychological and environmental obstacles that prevent us from moving from “seeing” to “doing.” For ministers, identifying these barriers remains a first step in helping a congregation transition from holding well-meaning intentions to living out habituated virtue.

1. The Boundary of the “Neighbor”

Among several obstacles that Dr. Oakes Mueller discussed four key concerns that limits compassion to our “neighbors.” The first obstacle to compassion surfaces through the concept of the circle of moral regard. Research suggests that the further an individual is from their own “in-group,” the less likely he or she possesses the ability to even observe the outsider’s signals of distress. People remain biologically and psychologically primed to meet the needs of those most similar to themselves, such as family or close friends.

To the extent that people categorize others as “them” or “out-group members,” they effectively move them into a “non-neighbor” category, which diminishes caring people’s sense of obligation. Furthermore, if people harbor moral judgments—believing someone’s suffering is deserved or the result of their own sin—the carer’s intuition to relieve that suffering is significantly dampened.

2. The Siege of Inattention and “Hurry”

In modern ministry, perhaps the most pervasive obstacle occurs through distraction and inattention. Dr. Oakes Mueller highlights that electronic media and the sheer pace of life have compromised ministers’ and congregants’ ability to maintain the focused attention necessary to see suffering in the moment.

When people live under high cognitive load—managing too many tasks or thoughts—they lack the mental energy to engage in cognitive empathy or perspective-taking. Drawing on the insights of Dallas Willard, Mueller suggests that a primary barrier to virtue occurs when people fail to “ruthlessly eliminate hurry” from their environment, as hurry prevents people from being present enough to recognize a neighbor in need.

3. The Fear of being Emotionally Overwhelmed

Another salient obstacle occurs through the lack of self-regulation, which leads to “distress at another’s distress” (DAAD). When a congregant sees someone suffering, but lacks the skills to differentiate their own feelings from the victim’s, they may “fuse” emotionally with the experience.

This fusion creates an egoistic or self-involved motivation to reduce one’s own internal arousal, often leading the person to flee, numb out, or cross to the other side of the street to protect themselves. Additionally, some may avoid compassion because they hold cultural narratives that frame care as a sign of weakness or vulnerability, making the emotional cost of connection feel too high.

4. The Mastery Gap: Lack of Behavioral Scripts

Finally, compassion often fails at the “doing” stage because congregants simply lack the procedural skills or “behavioral scripts” to intervene. A person may feel genuine sorrow but stay stationary because they do not know what a “first good step” looks like in a specific crisis. Without mentorship or role-modeling to provide these scripts, the perceived cost of helping remains high, and the potential for action is lost to uncertainty.

Participants might understand Dr. Oakes Mueller’s presentation of the obstacles to compassion as debris on a racetrack. The driver (the congregant) sees a clear destination (the value of neighbor love), but if the track is littered with the debris of distraction, the barriers of prejudice, or the fog of being emotionally overwhelmed, the car cannot reach the finish line. Clearing the track requires the habituated maintenance of virtue, which allows the driver to navigate these hazards smoothly.

Dr. Oakes Mueller’s presentations incorporated a number of additional key insights during the three hour webinar. The range of questions and responses revealed both a desire to cultivate compassionate practices among children and to help alleviate obstacles among adults who often work with children. The virtue of Compassion will appear during the coming Maker’s Space at Point Loma Nazarene University May 28-30. Many of the participants from the Day of Learning remain actively engaged fostering gratitude and trust with children. Hopefully the insights, which will be available through NTS Praxis, will inspire fresh strategies among children.

Pingback: Distinguishing Compassion | Discipleship Commons