Nurturing Care launched it’s third Maker’s Space retreat in Kansas City developing new prototypes to lead autistic children in worship and prayer practices. This year the gathering included churches from Texas and Oklahoma bringing the total participation to twelve congregations, twenty eight participants which gathered at the Marillac Retreat & Spirituality Center in Leavenworth, KS. all under the capable oversight of national coordinator Dr. Dana Preusch and our supportive team.

This gathering, known as a Maker’s Space (in honor of God our Maker in Psalm 95:6-7) serves as an invitation to try out ideas, name challenges, and find problems worth exploring rather than leaving with a “solution” to implement.

Director Dean Blevins frames the day as a lab, not a lecture. The task involves creating ministry prototypes—creative strategies to “find” solutions—then build partnerships within and across churches by utilizing mini-grants for a yearly plan. The rhythm invites an “early launch, ongoing follow-up:” including Zoom gatherings between major sessions to process learning, and several monthly reports that reads less like a spreadsheet and more like a spiritual snapshot—God sighting, humorous story, feedback from congregants—plus a mid-year learning session and a retreat update next year focused on one question: What can we learn?

“The Big idea,” Blevins says, “is to leave with a prototype to explore—not a solution to implement. Launch early. Learn as you go.” With this principle in mind, the group began to explore their empathy with autistic children by naming someone and exploring the Stories of these children and parents on the Journey into Autism.” The aim is pastoral and practical: help autistic children experience God through worship and prayer.

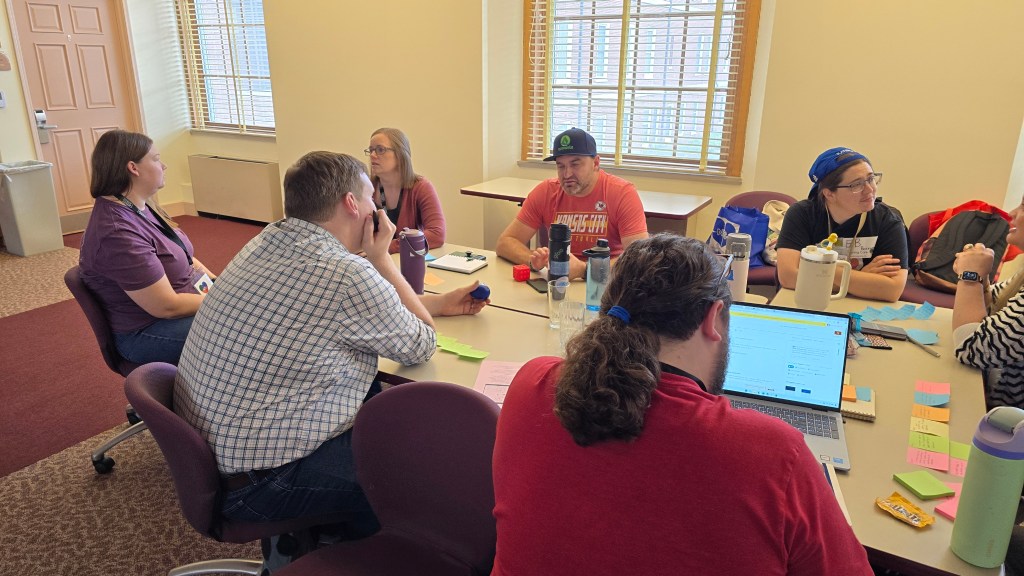

Next, the group began to explore the big issue of finding the real problem, which often hides behind the stated one. Working in small groups participants were encouraged to find “wicked-good problems,” where the problem remains fuzzy and the solution unknown, providing a challenge participants must build their way towards a solution through the prototype.

Participants were cautioned against “gravity problems,” or immovable constraints too large to solve. Participants understood they shouldn’t waste energy trying to fix the unsolvable but rather to rely on reframing problems by asking: given the constraints, what can we change? Throughout the event consultants offered a listening ear, offering grounded wisdom based on experience yet allowing participants to sort through their ideas.

To spark small group discussion and collaboration, participants were invited into divergent thinking. First, find an itch to scratch —name the problem that’s tugging at each person. Working alone the reflection begins to sprawl outward with Five Whys and mind maps to unpack the underlying problems. To help get at the wicked-good problem, attendees were invited to choose a hunch that addresses a barrier in worship or prayer, and then to ask “Why?” five times to generate multiple responses, yet resist the lure of straight lines.

Instead participants placed multiple answers into constellations and leaned into each other’s responses. “Track the steps your answers imply,” suggested Dr. Blevins “Where does the flow change direction? Where do participants expend energy? What needs to happen?” He urged the group to overlay experiences—to listen for patterns across stories, not just within one experience.

To expand potential solutions to work on, the group were prompted to open another door to possibility, each one phrased as a “How might we…?” tailored to their contexts:

- Question an assumption: What if children are already praying—we just don’t listen?

- Explore the opposite: What if children led us based on their prayers?

- Create an analogy: Do they need prayer guides—or imagery and safe spaces that reflect their world?

- Change the status quo: What if naming children’s presence helps the whole church pray?

As notes multiply, the group shifts the room from divergent to convergent thinking. The mind maps serve to create clusters of ideas—following Gestalt thinking—until crucial concerns surface, the ones that feel stubborn enough to be “wicked,” but practical enough to design around. “We’re not chasing a perfect answer,” Blevins reminds them “We’re looking for a workable one worth prototyping.”

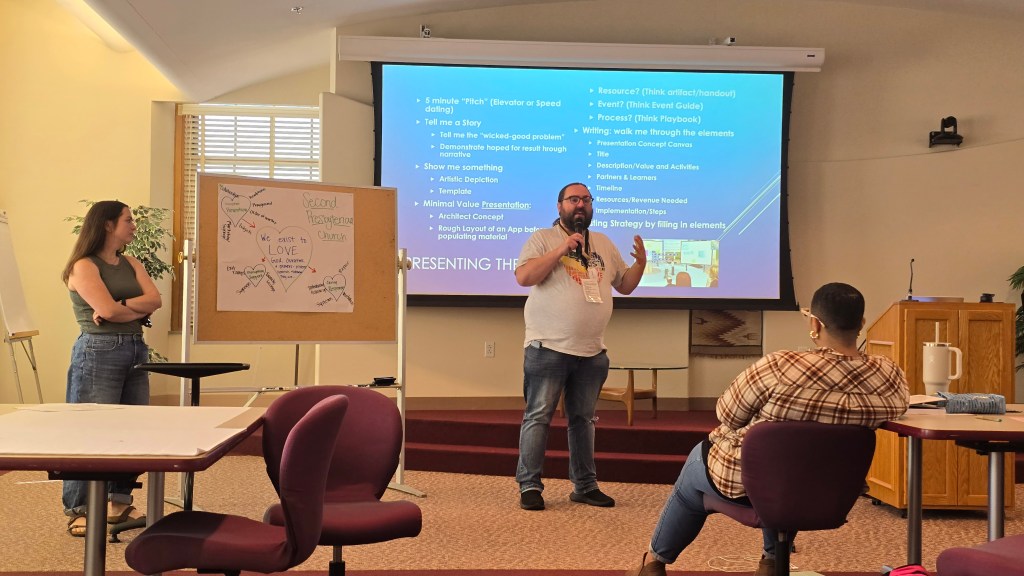

The group was next invited to ask the key question: “What if we build?” They were encouraged to think through their strategy much like they might metaphorically follow a blueprint, adapt one, or create as they go? All in all each team was encouraged to favor launching over planning. Define what the strategy they want and concretize it:

- Resource (an artifact or handout)

- Event (with an event guide)

- Process (a playbook)

As they closed out the evening each team was encouraged to lay out the steps—knowing more detail would come later—and don’t reinvent the wheel. The challenge included adapting to scale and context. Before the prototype was submitted they might talk to people including consultants who’ve tried similar work and Research (yes, Google). Blevins concluded that prototypes “let engineers and artists both contribute,” encouraging each team to consider “steps and flow.”

Day two begins in worship and prayer. Consultant and musician Emily Boresow melodically lead the group in song with the assistance of Consultant Janette Platter.

The song helped to settle the participants for a new day that included a devotional by consultant and chaplain Janette Platter. Chaplain Platter drew upon Julian of Norwich and Godly Play to introduce attendees to the middle spaces, like Norwich’s living space whose windows bridged the inner life of the congregation and a busy throughfare along the city’s main road. Using “I wonder” questions, Platter helped participants reorient their tasks in the spirit of prayer and ministry.

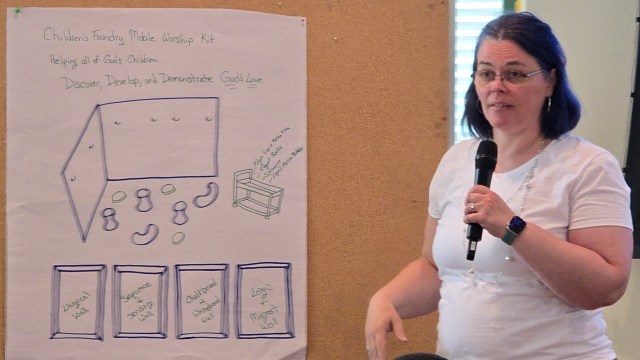

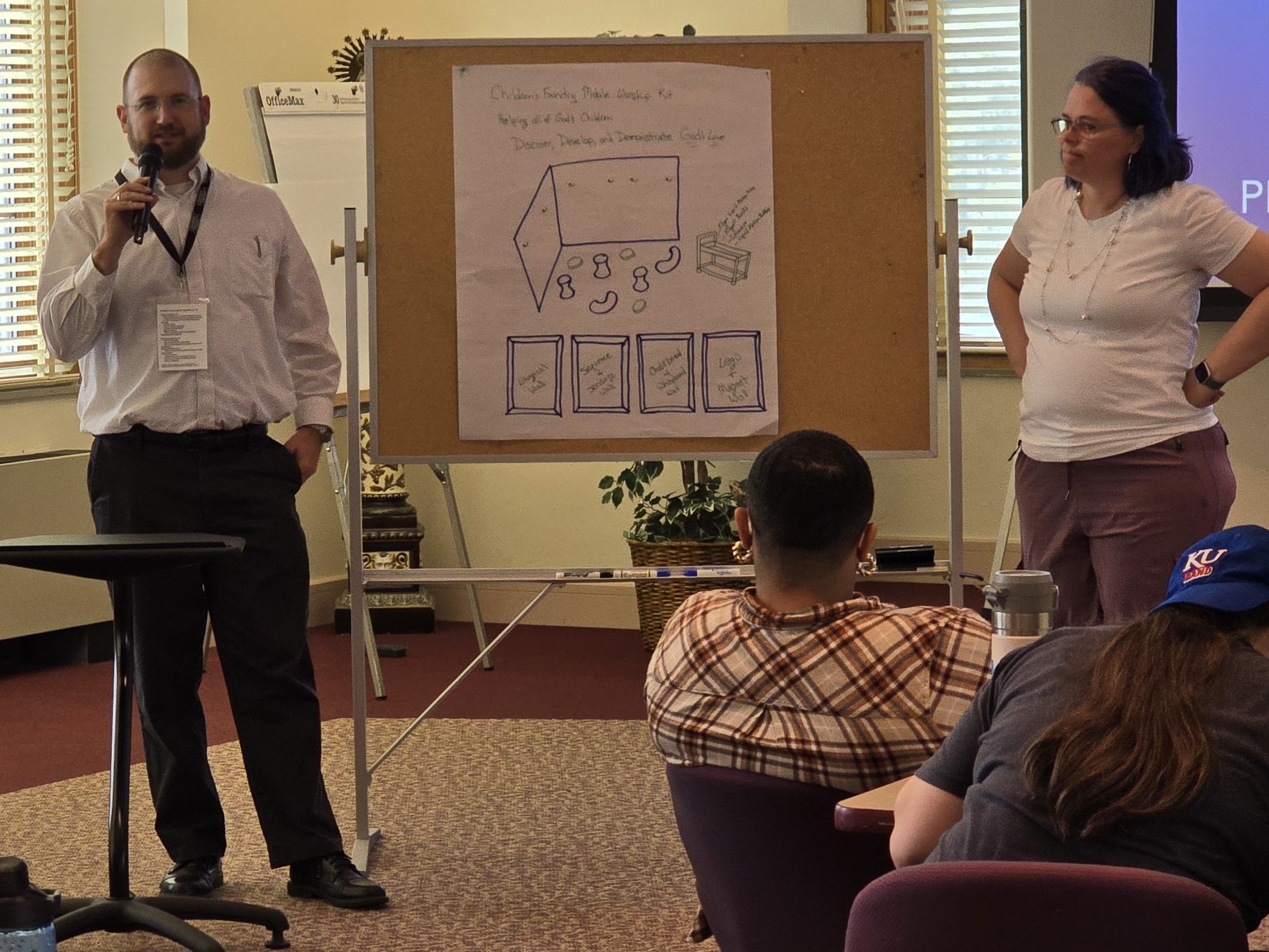

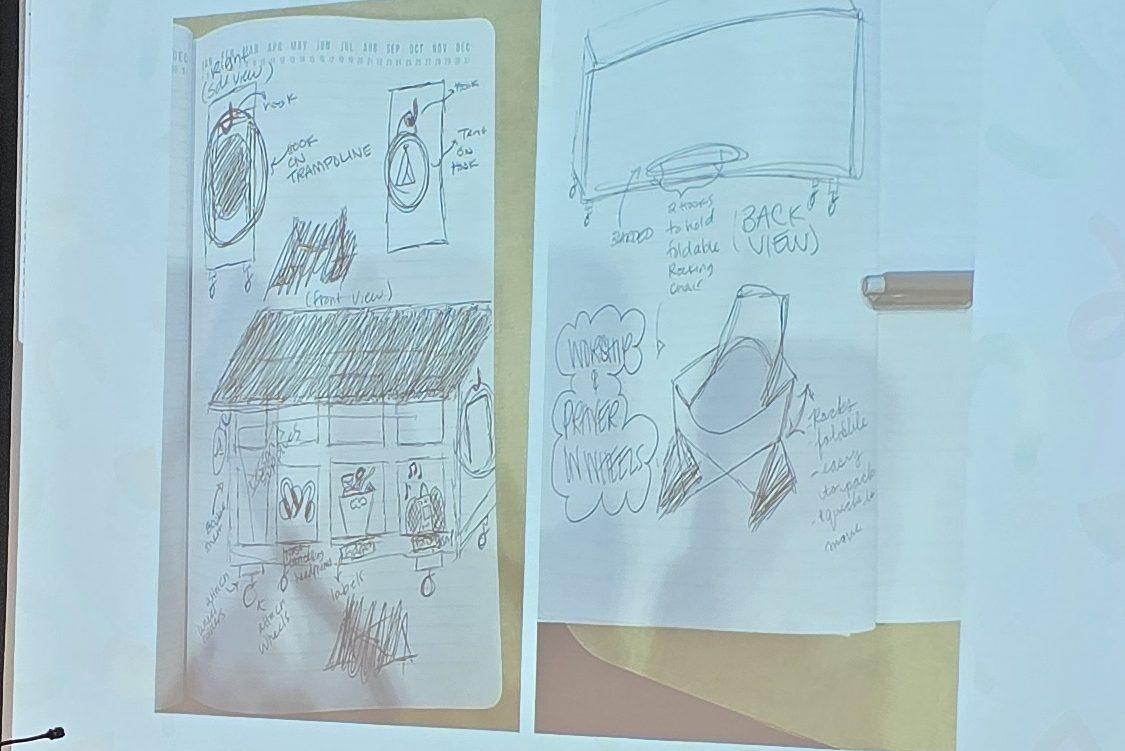

The rest of the group time to expand on the work started the night before and to present an initial strategy. Each team received five minutes to provide an an elevator pitch through several prompts including: Tell a story. Name the wicked-good problem. Demonstrate the hoped-for result through narrative. And show something—anything that makes the idea visible: an artistic depiction, a template, or a minimum-value presentation—an architect’s concept, a rough app layout before content, a sketch of a resource, event, or process. “Walk us through the elements,” Blevins says, pointing to the Presentation Concept Canvas as a framework to begin creating artistic renditions. Throughout the community-generated posters and presentations, every participant focused on making worship more inclusive, engaging, and accessible, especially for children and neurodivergent participants. Several common themes occurred including,

- Creating inclusive, sensory-friendly worship spaces;

- Actively engaging children (especially neurodivergent) through movement, tools, and structured play;

- Providing resources like kids’ bags, classroom adaptations, sensory tools, and playbooks;

- Building community through collaboration, training, liturgy writing, and intentional responses; and

- Using creativity (gaming, storytelling, relatable heroes) to connect kids to faithThe materials collectively emphasize creativity, sensory awareness, collaboration, and the reshaping of both worship practices and physical spaces.

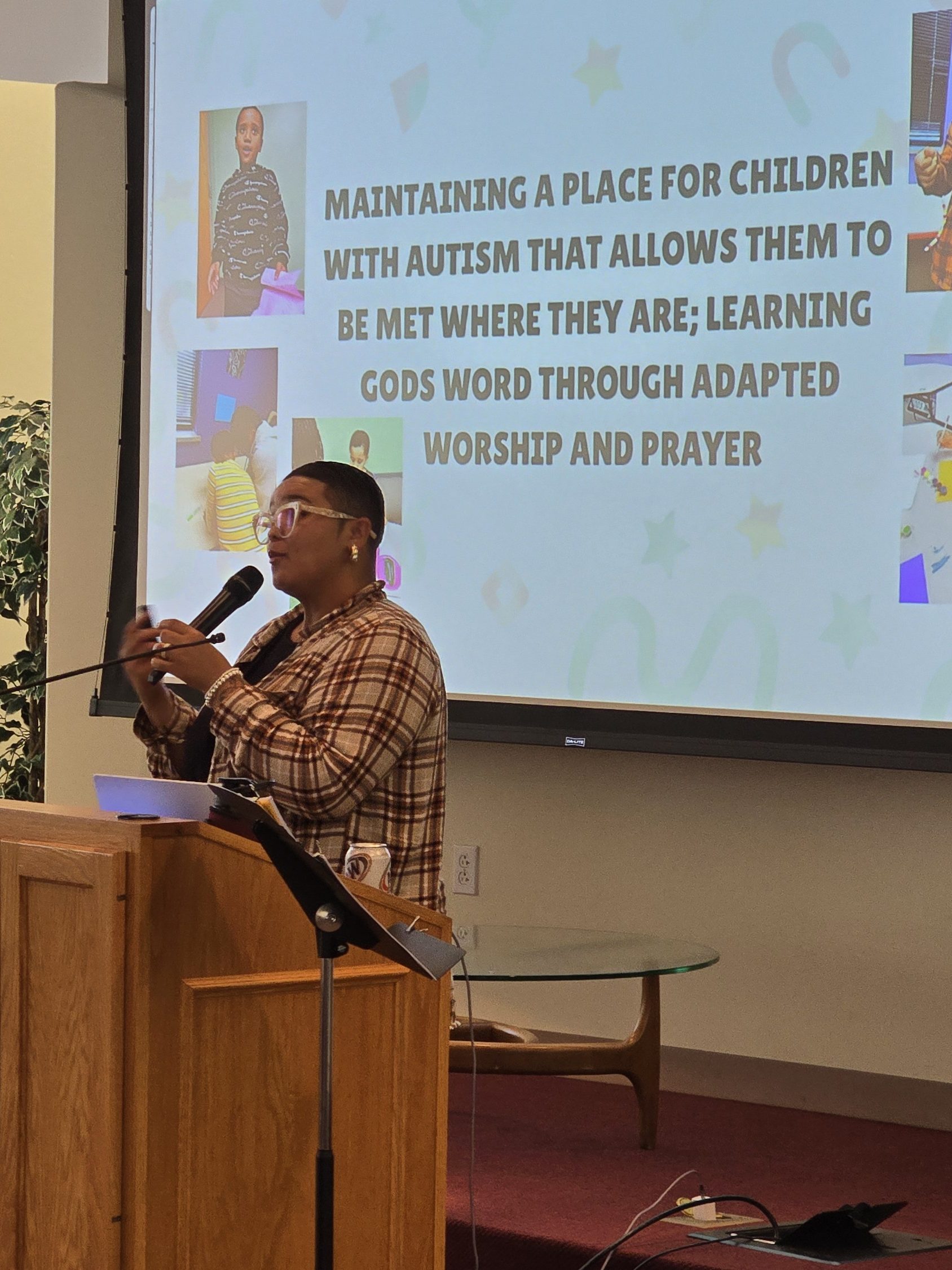

Sacred Play: Inviting All Neighbors to Worship

The Sacred Play initiative centers on designing worship where all neighbors are welcome. The plan calls for collaboration among staff, parents of neurodivergent children, therapists, and teachers. Each group contributes to worship through music, responsive readings, storytelling, prayer, and Eucharist. A recurring theme is flexibility — beginning services around the church seasons, adjusting timelines, and refining practices through trial and error. Implementation includes practical steps like writing liturgy, buying supplies, and holding meetings with children and parents.

This project positions worship not as a rigid program, but as a living space where diverse expressions are recognized and embraced.

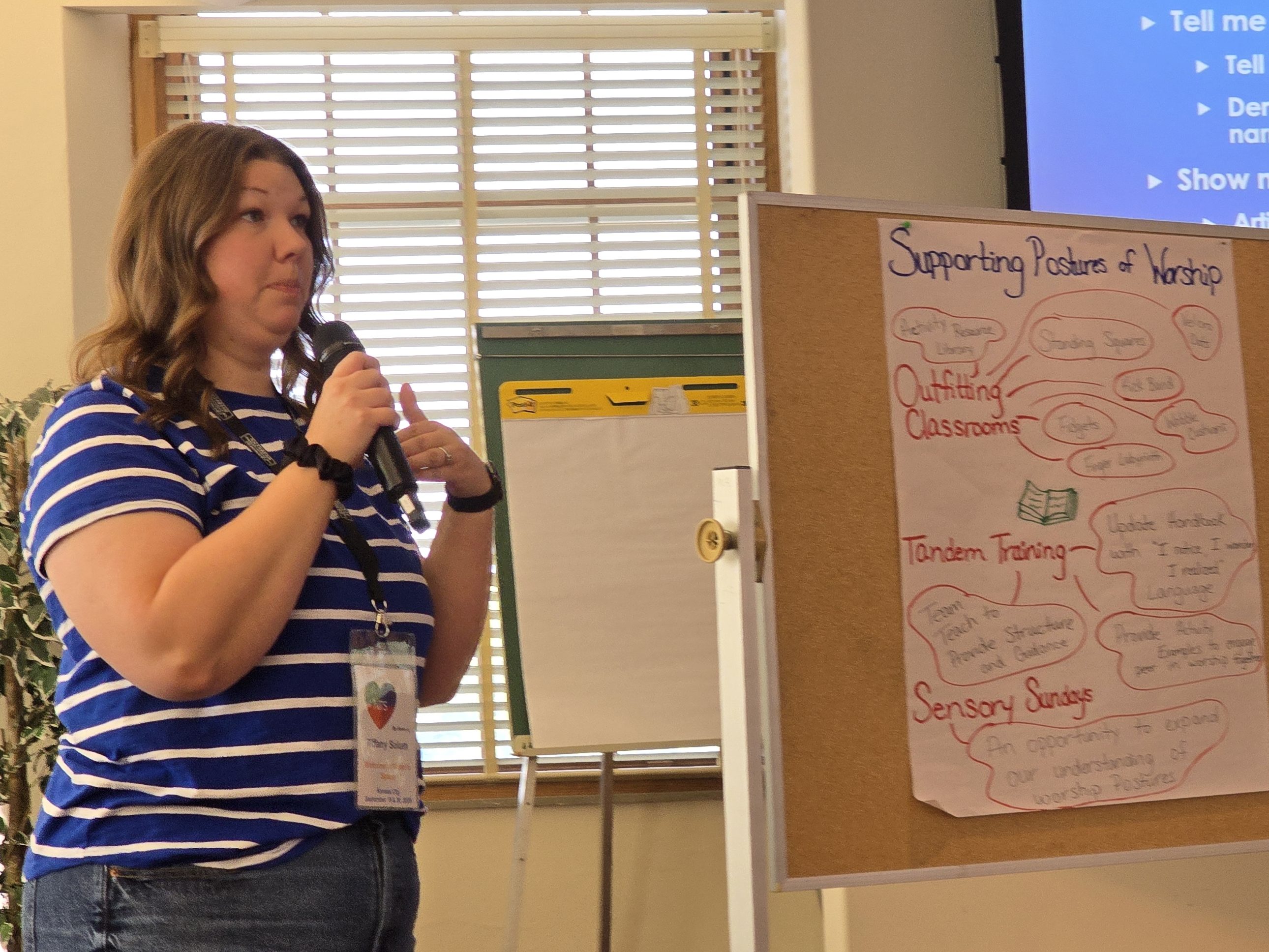

Supporting Postures of Worship

Another set of ideas focused on worship postures and physical supports. Suggested adaptations include standing squares, velcro dots, fidgets, wobble cushions, and finger labyrinths — small but meaningful tools to help participants remain engaged. The posters also highlighted “Tandem Training,” where teams of leaders model and provide structured guidance. Updating handbooks with reflective language (“I notice, I wonder, I realized”) reinforces sensitivity to experience.

“Sensory Sundays” were proposed as opportunities to broaden the community’s understanding of how posture, tools, and space shape worship participation.

Spaces, Bags, and Communication

One presentation broke ideas into four quadrants: space, kids’ bags, foyer welcome walls, and communication. Space planning sketches showed reconfigured layouts to make worship rooms more navigable. Kids’ bags were proposed as resources filled with items for auditory, visual, social, and sensory needs — as well as drawing pads to foster expression. The foyer welcome wall envisioned a space to greet families with clarity and encouragement. Communication included visual supports, websites, and children’s ministry messaging to keep families connected.

Together, these measures illustrate how careful preparation of both space and resources can create a more hospitable worship environment.

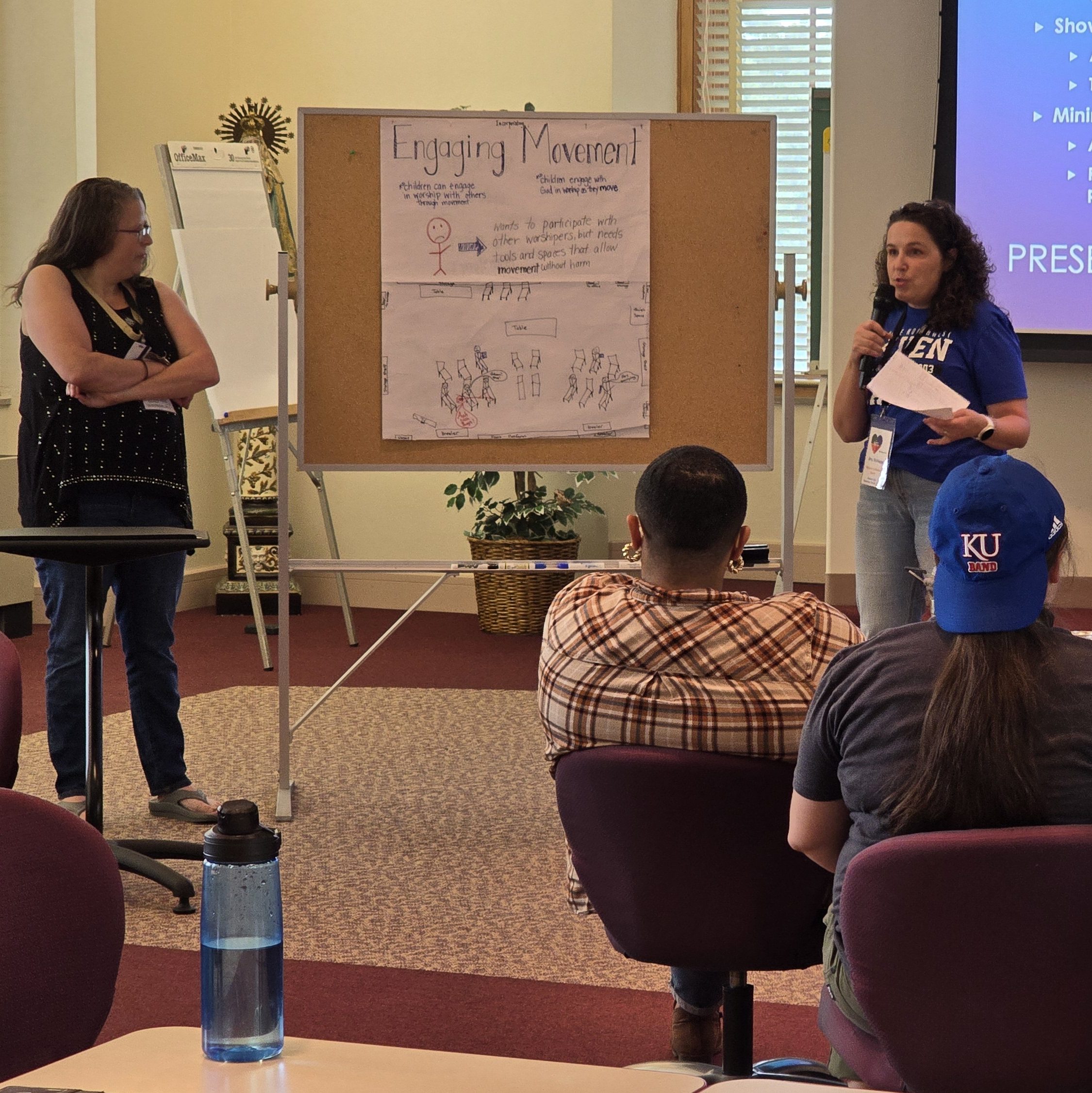

Movement as Worship

Several posters emphasized movement as a pathway to participation. Children can engage both with others and with God through embodied practices. However, they require safe and appropriate spaces to move without disruption or harm. Suggested adaptations included creating quiet corners, sensory activity tables, and clearly designated areas for kneeling or storage.

The message was clear: movement should not be viewed as a barrier to worship but as an essential form of participation.

Caring, Prevention, and Response

One community vision came from Second Presbyterian Church, which declared: “We exist to love God, ourselves, and others — whoever, however, wherever they are.” Around this statement were clustered three commitments: prevention of disruption, support during disruption, and caring response afterward. Concrete strategies included signage, family lounges, headphones, playground spaces, exit ramps, and clear follow-up systems.

This framework moves beyond tolerance toward proactive design, ensuring every participant feels cared for before, during, and after worship.

Playful Engagement: Engaging God Mode

Another creative set of ideas reframed discipleship as play. “Godly Gaming” suggested biblical role-playing games, strategy card games, and activities like cooking or athletics to draw youth into spiritual exploration. “Relatable Heroes” envisioned online videos, print-on-demand resources, and age-specific programming for younger and older children. These efforts would occur both in church and at home, bridging faith and daily life.

This playful approach emphasized that spirituality can be deepened through creativity, storytelling, and connection to familiar cultural forms.

Playbooks for Belonging

Two posters highlighted the value of structured playbooks. Created to Belong – NH proposed a framework including parent intake, volunteer guides, resource lists, classroom experience models, and feedback loops. Beautiful Journey focused on autistic children, suggesting 5th Sunday Worship Services tailored to comfort and adaptability, listening groups for feedback, and specialized training for families and community members.

Both playbooks emphasize adaptability, feedback, and ongoing training — essential for building intentional and supportive communities.

The Practice of Space

One final poster offered a conceptual reminder: “The practice of space and the space of practice.” A cube hovered above stick figures, with arrows showing interaction between the environment and the community. This simple diagram reinforced the theme present throughout all presentations: worship spaces shape practice, and practice, in turn, reshapes space.

Another prototype wrestled with providing space in temporary worship settings. Recognizing that often autistic kids love interaction, but also need resources, the proposal named both the blessing of each child while also proposing a portable storage “space” that could house items but also serve as an interactive framework.

Two questions stand like guardrails at the exit:

- Can you find partners to make it happen? This is the “come-to-Jesus moment.” Who will you partner with—consultants, participants, people in your church? Keep it manageable. Will you obtain or adapt resources?

- What will you learn from the prototype? Not just works/doesn’t work, but what did the doing teach you? Be ready to adapt, adopt, tweak, or start over.

The day closes the way it began: with a plan for ongoing collaboration. After launch come the three to four inter-session gatherings, the monthly reports—again: God sighting, humorous story, congregant feedback—and the monthly meetings to process learning. There’s a mid-year check-in and another learning session, then a retreat update next year to harvest the lessons. The hope, by then, is modest and ambitious at once: real problems with working solutions—not the illusion of certainty, but the practice of faithful, tested love.

As laptops close and chairs scrape back, a participant snaps a photo of the final slide. In the image, one line lingers like a benediction—and a brief: Leave ready to try.

Conclusion

Taken together, these projects reflect a vision of worship and prayer that is inclusive, playful, and deeply community-driven. The posters encourage churches to:

- Prepare sensory-friendly environments.

- Provide resources for engagement (bags, fidgets, cushions).

- Honor movement as a valid form of worship.

- Develop playbooks and training for consistency and support.

- Use creativity and cultural tools (games, stories, videos) to connect children and youth.

- Build systems of prevention, care, and response.

The consistent theme of Design thinking encouraged participants to not look for perfection, but embrace practice: trying, adjusting, and trying again. In this way, communities move closer to embodying worship and prayer where autistic kids find a place where all truly belong.

Pingback: Nurturing Care 2025 Retrospective | Discipleship Commons