This Nurturing Care article explores how churches can minister to and worship with neurodiverse individuals. Drawing on recent presentations, the writing challenges assumptions of normative worship, advocates for belonging before belief, and calls the Church to recognize neurodiverse members as spiritual saints already shaping congregational life.

Introduction

In an age when belonging is increasingly celebrated, the Church is still learning how to embrace all its members—especially those who are neurodiverse. Two recent presentations at both the New England District and Northwest Nazarene University’s PALCON offered one response by Dr. Dean G. Blevins, Director of Nurturing Care. Two workshops, titled “Ministry on the Spectrum” and “For All the Saints,” explored this growing frontier of prayer, pastoral care, and inclusive worship, raising essential questions about what it means to be the body of Christ in a world full of cognitive, emotional, and sensory differences. The following essay reflects a summary of those presentations for our current consideration.

The Challenge Before Us

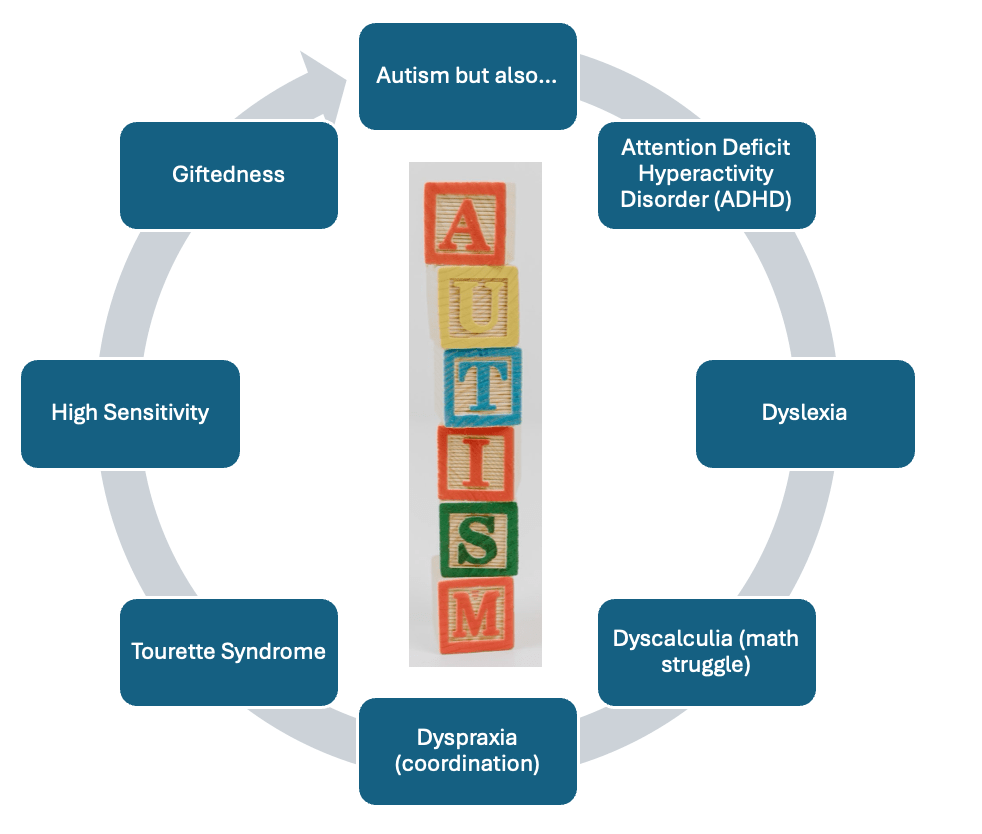

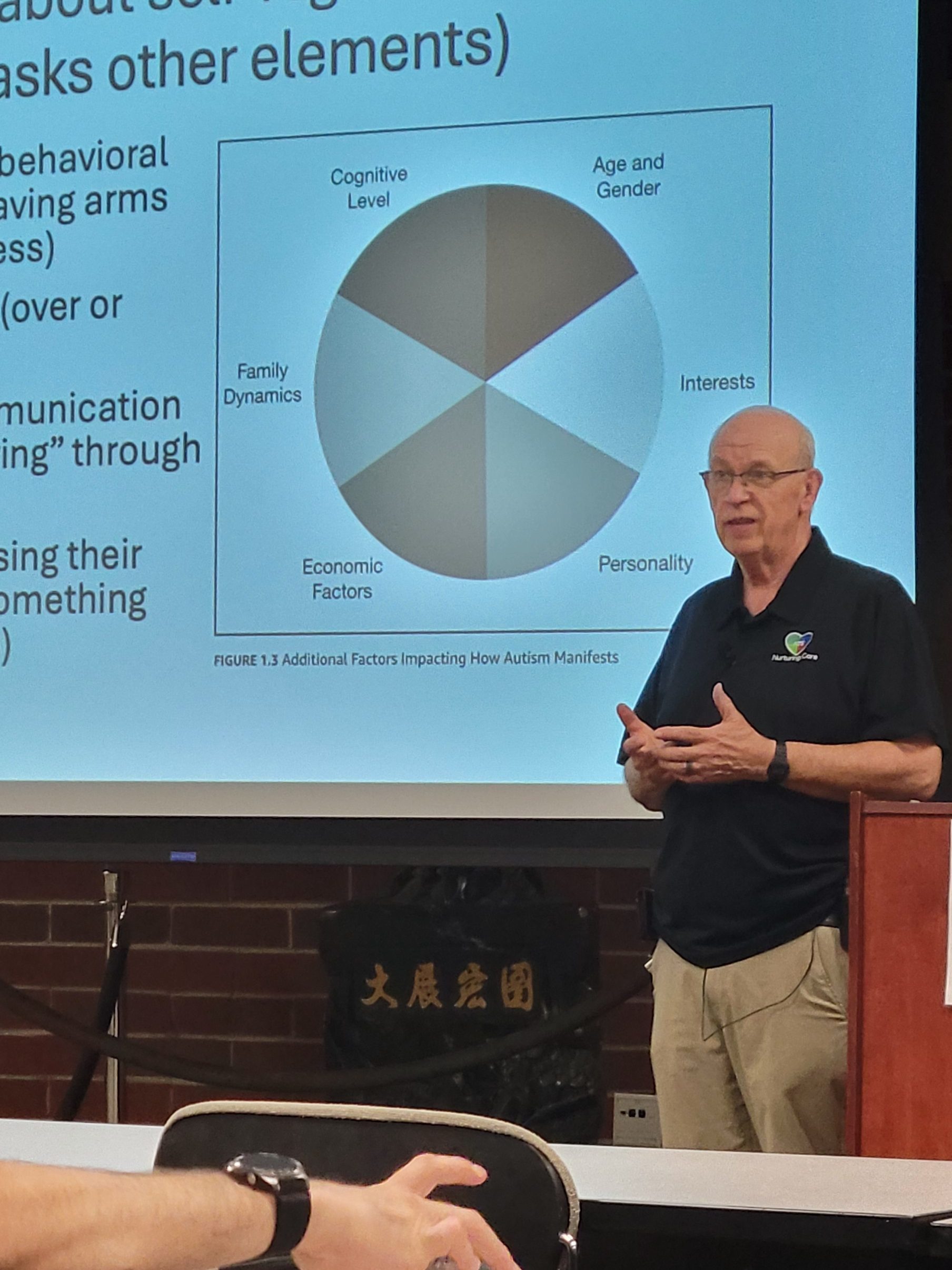

At the heart of both presentations rests a challenge: How do we minister to and worship with people who process the world differently? Pastors recognize that autism spectrum disorder (ASD), along with other neurodiverse conditions such as ADHD, dyslexia, dyspraxia, and high sensitivity, increasingly appear in our congregations. And yet, church responses often lag, leaving children, parents, and a growing number of adults masking their conditions or staying home. As Temple Grandin reminds us, autism is not a monolithic condition, but a spectrum of experiences shaped by unique cognitive and emotional processing patterns.

When churches try to simplify, or generalize, neurodiverse experiences, they risk misrepresenting or marginalizing individuals who are, first and foremost, people—people with their own personalities, stories, and strengths. People who bring personal traits, live with emotional states, and often must deal with really different experiences. We are reminded, “When you’ve met one person with autism… you’ve met one person with autism.”

The Myth of Normativity

The presentations push us to examine our underlying assumptions. Who gets to decide what “normal” looks like in worship? Evangelical worship culture, often influenced by popular Christian music and emotional expressions of piety, risks promoting a single “authentic” experience of worship. But what of the child who flaps their hands in delight or the adult who wears noise-canceling headphones due to sensory sensitivity? Are these behaviors signs of spiritual disconnection—or alternate expressions of embodied worship?

Drawing on the work of scholars like Tom Reynolds and Leon van Ommen, the presentations challenge the “myth of normativity” in worship. They ask whether our liturgical and architectural designs—often intended to foster a loud, lively, worship, or ornate beauty—may unintentionally exclude those who engage the world through different sensory or cognitive frameworks.

From Exclusion to Embrace

Too often, churches respond with a “garbage can” approach to inclusivity, fearing that they must begin with a wide array of somewhat undefined needs, unclear goals, and unprepared parishioners, that can prove daunting. This approach can result in a blanket approach, or blanket fear, that results in outsourcing neurodivergent children to sensory rooms, or worse, ignoring their needs entirely assuming the task remains too large for the congregation. But what if inclusion wasn’t an afterthought? What if the presence of neurodiverse individuals was seen not as a disruption, but as a gift?

The Catholic tradition, with its literal incorporation of saints into worship, provides a helpful lens. Saints are not honored for their perfection, but for their faithfulness, often in the midst of frailty, difference, and profound struggle. Even the Protestant tradition continues the idea of sainthood, often through grand gestures like naming buildings in honor of people, or more simple expressions of hearing about the “saints” through a memorial role. Yet, saints can embody a different kind of “unique” piety, outside the normal expressions of the congregation. Figures like Saint Symeon the Stylite, who lived atop a pillar for decades, and Richard Rolle, who’s mystical, but unsettling, experiences puzzled even his family, suggest that “oddness” and “holiness” may not be strangers. Likewise, neurodivergent individuals—children and adults alike—may possess unique spiritual insights and expressions that can enrich the entire congregation. Usually even “everyday” sainthood requires a community of support, space that acknowledges the presence of these unique individuals, and leadership to name the giftedness of these people in the middle of the congregation.

Belonging Before Believing

A recurring theme throughout the presentations was the need to prioritize belonging before believing or behaving. This means designing church spaces and relationships where people are welcomed as they are, not as we wish they would be. It also means moving beyond accessibility audits and asking deeper relational questions. Do our congregations signal receptivity, or merely compliance? Are we building relationships that honor identity, voice, and agency? Dr. Blevins noted that beyond ADA compliance, churches should conduct a “relational audit” of congregants comfortable with encountering people on the spectrum.

This shift in awareness and posture requires adaptive thinking. Sensory spaces, for example, should be about connection—not containment and exclusion. Worship should be embodied in ways that allow people to express faith as they understand and feel it, even if their responses surprise us. The message of the gospel remains unchanged, but the mode of delivery may need to adapt.

Every Church a Place for Saints

The final invitation of both presentations included an invitation to recognize the saints among us—not those who are perfect, but those who stretch our imagination of what the Church can be. Neurodiverse individuals often show remarkable resilience and grace as they navigate a world not built for them. Many are already accommodating church practices more than the church is adapting to them.

So, who are the saints in your church? Who challenges you to rethink what worship looks like? Who teaches you about joy, perseverance, or unspoken prayer through their presence?

Naming these people—not as problems to be solved but as members of Christ’s body to be cherished—is a first step toward building a truly inclusive church. A church where everyone can worship in spirit and truth. A church that remembers the words: “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness” (2 Corinthians 12:9).

Next Steps: Think Adaptively

To truly welcome neurodiverse individuals, churches must get creative. Consider partnerships with disability ministries and local organizations. Make use of resources like the Wonderful Works Adapted Library part of the Church of the Nazarene’s new Disability Ministry, expressive of the new collaborative known as the Nazarene Adaptive Network that Nurturing Care has joined. Above all, be willing to stretch. Perfect inclusion may not be possible—but perfect love is.

As one guiding phrase from the presentations reminds us: “Nothing about us without us.” Inclusion isn’t about programs; it’s about people. And it starts by seeing the saints already seated in our pews.

Dr. Blevins is available to present these workshops in other settings. You may contact him through Nurturing Care by emailing info@nurturingcare.org

See also our upcoming Preachers Conference addressing “All God’s Children” September 23-24, 2025 at www.nts.edu/preach

Pingback: Nurturing Care 2025 Retrospective | Discipleship Commons

Pingback: Preaching on the Spectrum | Discipleship Commons

Pingback: A Season of Nurturing Care | Discipleship Commons